The stories we experience as children become woven into the fabric of our being. This valuable form of entertainment not only stokes our childhood imagination: it transports us to new, unbelievable worlds. Stories prepare us to navigate life, society, and give us an appreciation of our own cultural heritage as well as that of others.

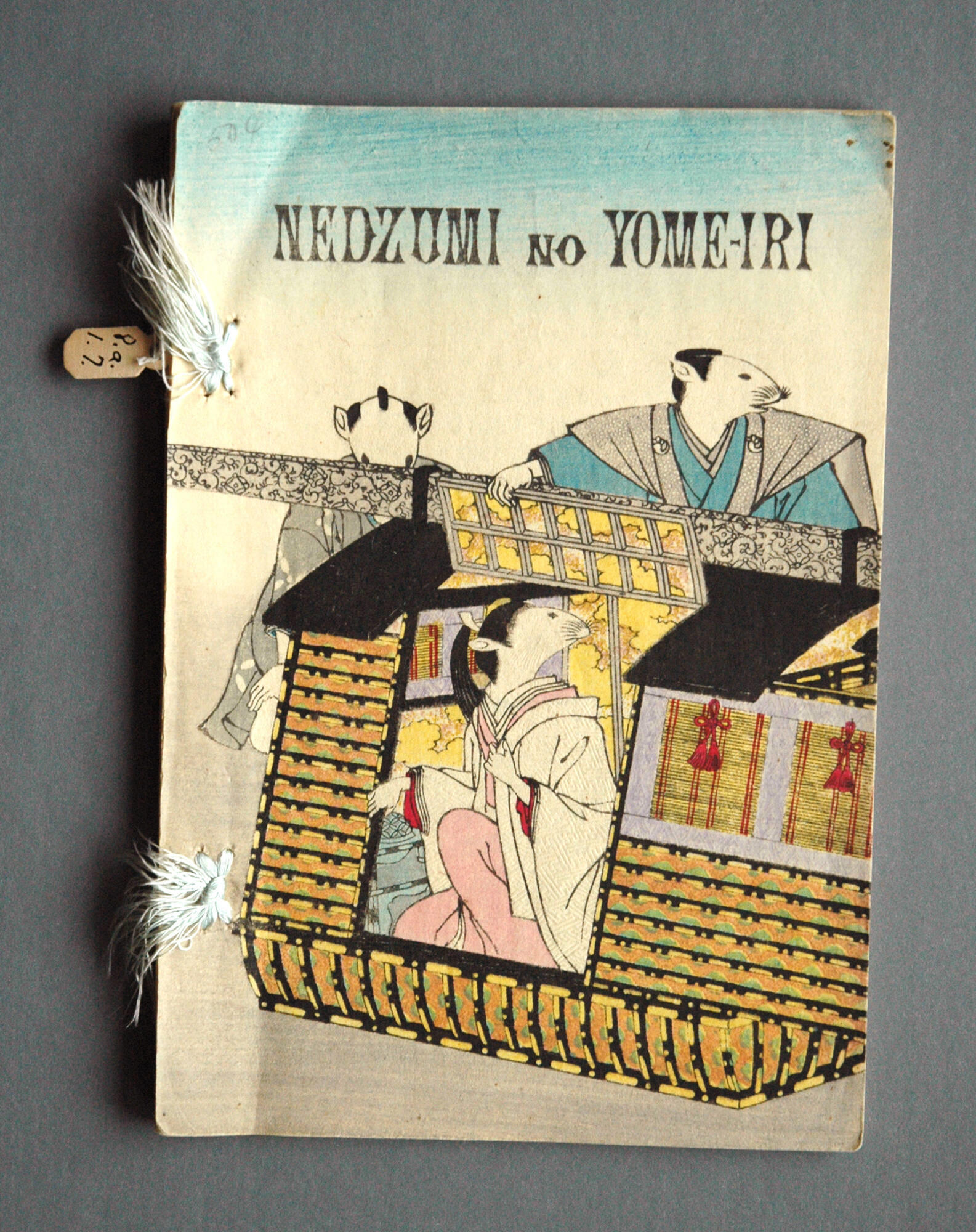

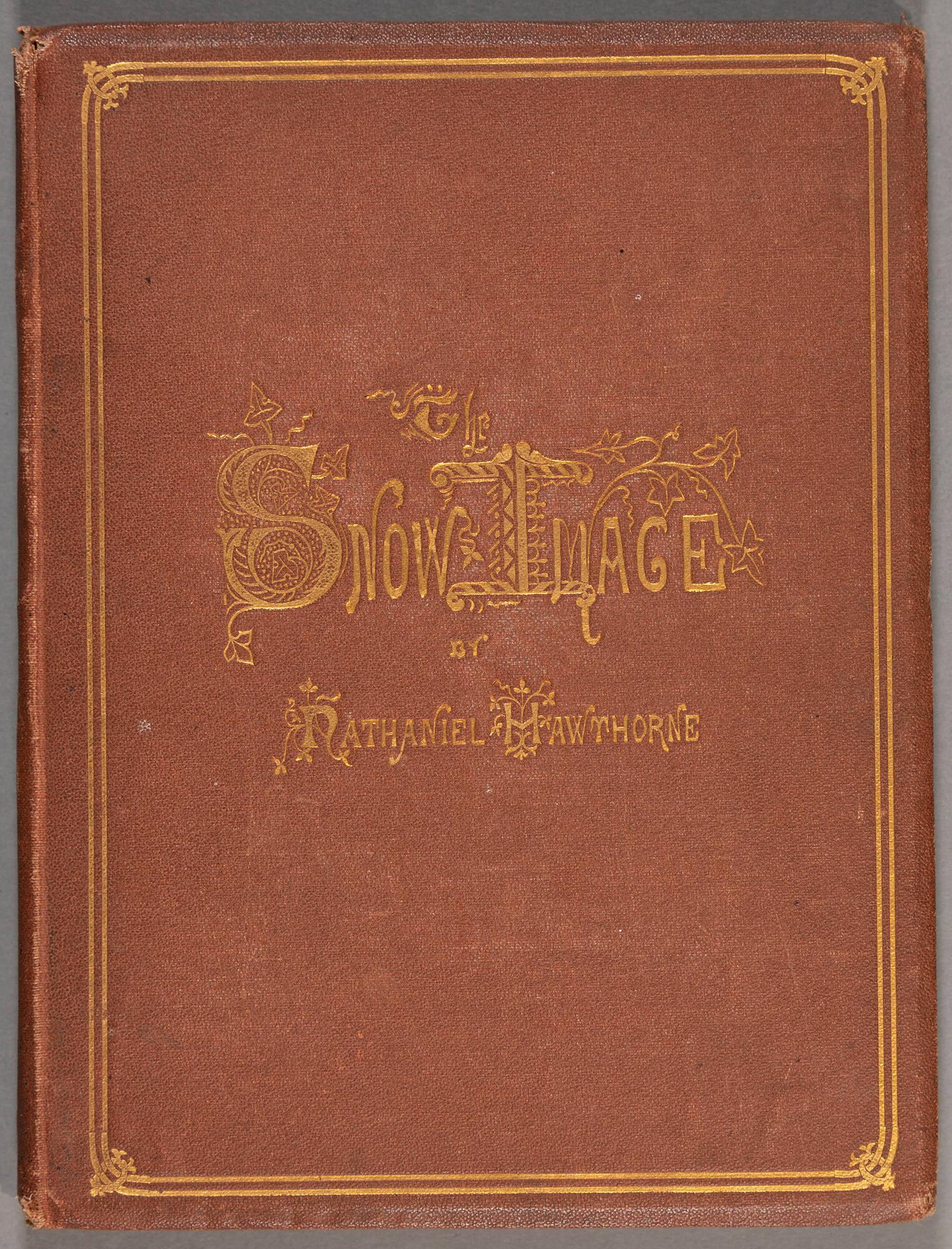

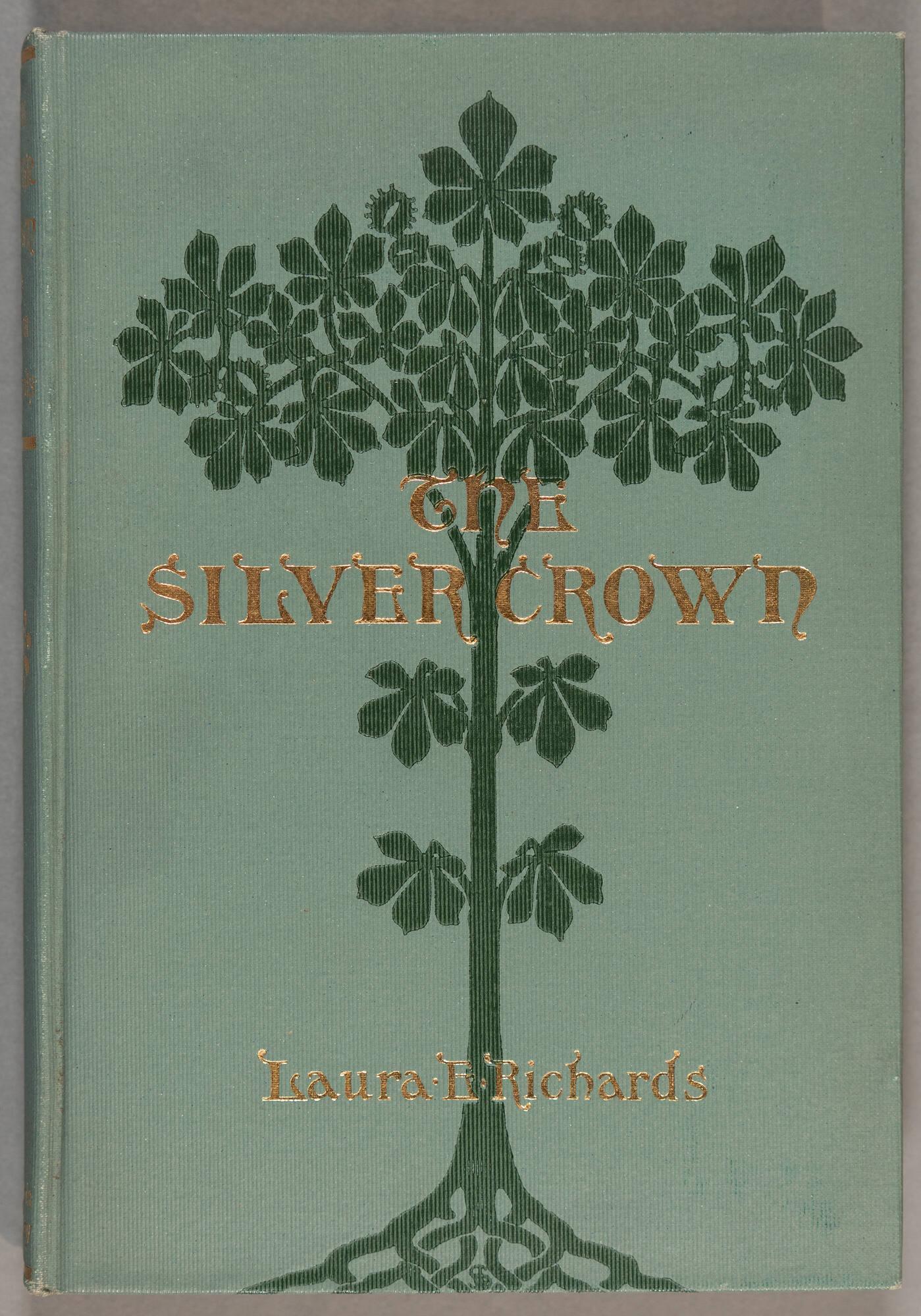

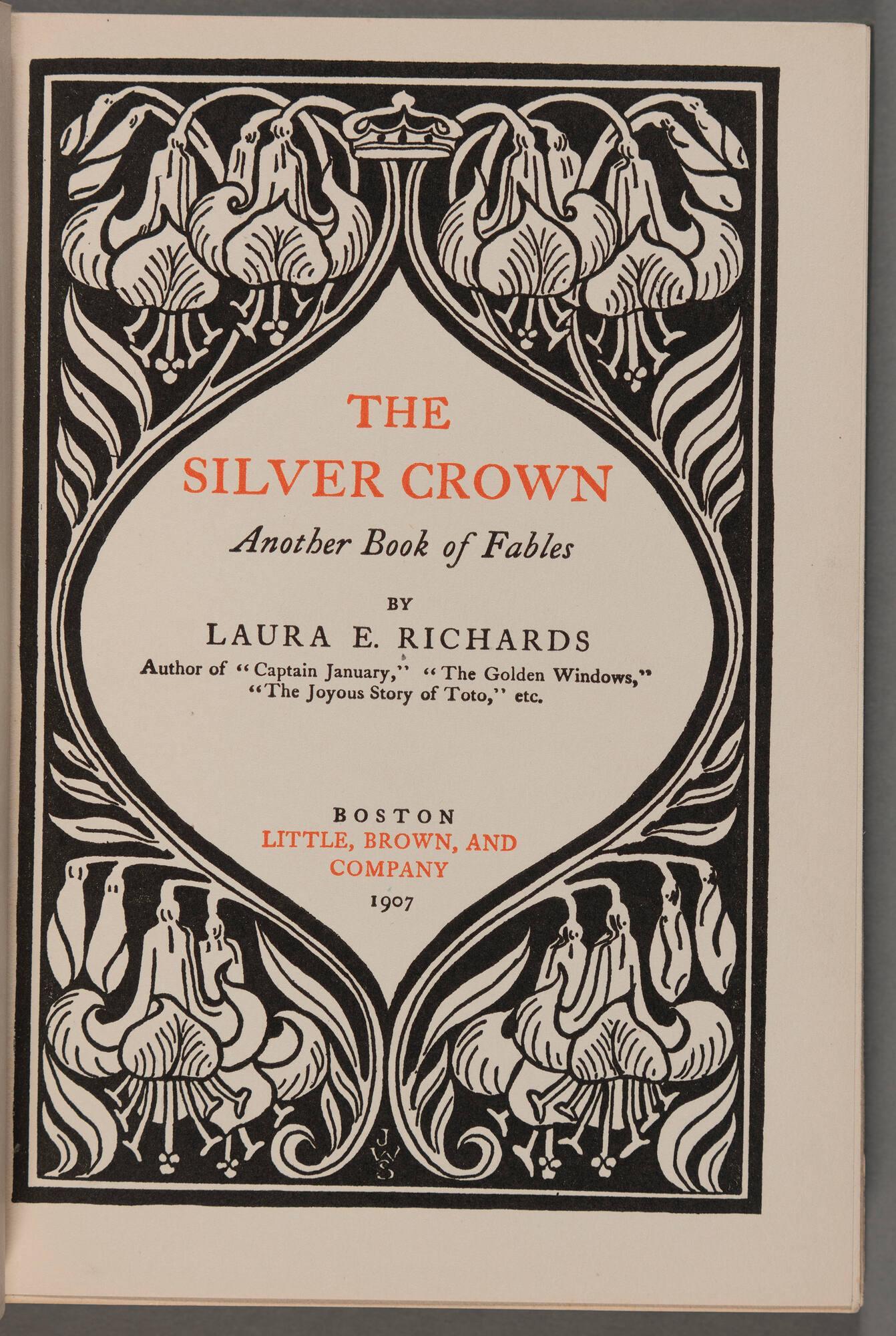

Children’s stories began as folklore passed through oral traditions. Fables, fairy tales, proverbs, and creation myths later expanded to paper editions that were printed, illustrated, and distributed. Today, the genre of children’s literature has morphed into a behemoth of its own, with many books becoming highly sought-after collectible items.

Isabella’s Collection of Children’s Books

Before she collected paintings, tapestries, furniture, and sculptures, books captured Isabella Stewart Gardner’s attention. Between 1886 and her death in 1924, she purchased approximately 3,000 books and manuscripts spanning six centuries.

Roughly 120 of these volumes are books written or adapted for children. They include some of Isabella’s own childhood books, others that she collected, and books she bought for her orphaned nephews. She and her husband raised Augustus Peabody Gardner, William Amory Gardner and Joseph Peabody Gardner after their father’s death in 1875.

Nari Ward’s Inspiration

Artist-in-Residence Nari Ward (b. 1963, St. Andrew, Jamaica) saw Gardner’s collection of children’s books as an “entry point” into the Museum during his month-long residency in 2002. Visitors often overlook this area of the collection. But it became the catalyst for Bus Park, a new interactive work he constructed and exhibited at the Gardner the following year.

In researching the Museum, I got intrigued with the things that weren’t visible and the things that the public didn’t have access to. There are a whole slew of books that fit this category, and one particular group are the children’s books. I am a storyteller at heart in terms of finding my materials and trying to find different narratives behind them. I think that was why I was attracted to them.

— Nari Ward

Like all good storytellers, both Isabella and Nari Ward knew how to capture our imaginations by combining visual art, sound, and performance to create rich, multidisciplinary environments.

Ward makes his internationally-known sculptural installations out of unnoticed or discarded and found materials. He re-contextualizes these items in thought-provoking juxtapositions that create complex, metaphorical meanings. His pieces confront social and political realities surrounding race, migration, democracy, and community. At the Gardner, it was the story books, housed unseen in various bookshelves around the Museum, that fired his imagination.

Once I had the books all together, I decided I wanted to just use the beginnings of the books. I think primarily it was for me about potentiality. You know, when you start to hear a story, you really get intrigued with what the story is. That is the most alert you will probably be during the course of the story and I wanted to bring this state of alertness and potentiality into the project.

— Nari Ward

Ward’s Bus Park

Ward selected the first two sentences from eighteen children’s books and invited a group of students from the Boston Arts Academy to record them. He edited the recordings to create a whimsical sound piece that played on a loop inside of Bus Park, a small yellow school bus that Ward transformed into a stationary and imaginary entrance to the Museum.

He said about the project:

When you sit here and you listen to all the beginning statements from these stories there is an expectation of it going someplace, but they really never go anyplace. What they bring up are different images. Either images that are directly linked to the story or images for yourself in terms of memory. There were some children’s books that I remembered and I really wanted them to be a part of this. I like the idea that an adult would remember, or a child, when they are listening to the stories being read in the bus. They would remember, ‘Ah, that’s Alice in Wonderland’, and that would be another tangent that they could engage in while they are sitting in this space.

Ward positioned the bus on the Museum’s grounds where visitors could access it from the main building through a small door in the garden wall. In addition to making the soundtrack, Ward decorated the interior of the bus to mimic the pink and white speckled walls of the Courtyard, and reupholstered the seats with barrier landscaping cloth. He included a photo album on each seat that featured photographs taken by the Arts Academy students when they visited the Museum. He also covered the exterior in an elaborate bramble of pencils and zipties that grew out of flower pots fastened along the frame of the vehicle.

The garden wall door through which visitors would access the bus at the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum.

Watch the video of Nari Ward making Bus Park, (06:18) Film credit: Mark Lipman

This network of pointy objects evoked the barrier of thorns that blocked Sleeping Beauty from the outside world. However, this barrier also touched on something thorny closer to home. The school bus is an emblem of American education and childhood. It also symbolizes the violent history of desegregation in our public school systems.

I was also very aware of the history of busing in Boston and I wanted to kind of bring this social history into it as well in a kind of mischievous way, without it being a political work. So, it has the full range of being very playful and fanciful and also having this undercurrent of a kind of a problematic history within Boston itself.

— Nari Ward

Ward used Bus Park to remind us of the unequal distribution of academic resources, such as books. His installation highlights marginalized communities and the history of this unequal treatment in Boston. An artist's exploration into Gardner’s collection of children’s literature became a project spanning the past and the present. It asked us both to reflect on the stories that we remember as children and on the stories we see in the broader social landscape as adults.