Nestled in a niche under the staircase in the West Cloister is an extraordinary stone cenotaph from fifteenth-century Afghanistan. Made from a single piece of dark gray stone, the grave marker bears calligraphic writing in Arabic, including invocations to God (Allah), and vegetal, floral, geometric, and cloud designs, some inspired by Chinese sources. The extensive program of inscriptions and ornamentation served to endow the now-unknown deceased—most likely a noble or elite affiliated with the Timurid dynasty (1370–1507)—with divine protection and spiritual blessing.

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston. Photo: Sean Dungan

The West Cloister with the Persian cenotaph (S12w2) nestled under the stairs

Knowledge of the stone’s funerary function likely eluded Isabella when she purchased it from the Paris-based dealer Mihran Sivadjian in 1901. A letter to Isabella penned by Sivadjian that year described the Islamic cenotaph as a “truly remarkable work of sculpture,” but made no mention of the object’s commemorative purpose.1 The manner of the cenotaph’s installation in the West Cloister—in an upright position as opposed to recumbent, as custom dictated—suggests that this information was of secondary importance. For Sivadjian, as for Isabella, the object’s stunningly executed designs, rather than its historical or cultural context, seem to have been the main draw–and for good reason.

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston (S12w2). See it in the West Cloister.

Persian, Herat (Afghanistan), Fragment of a Cenotaph, about 1475. Likely schist, 114.3 x 36.2 x 32.4 cm (45 x 14 1/4 x 12 3/4 in.)

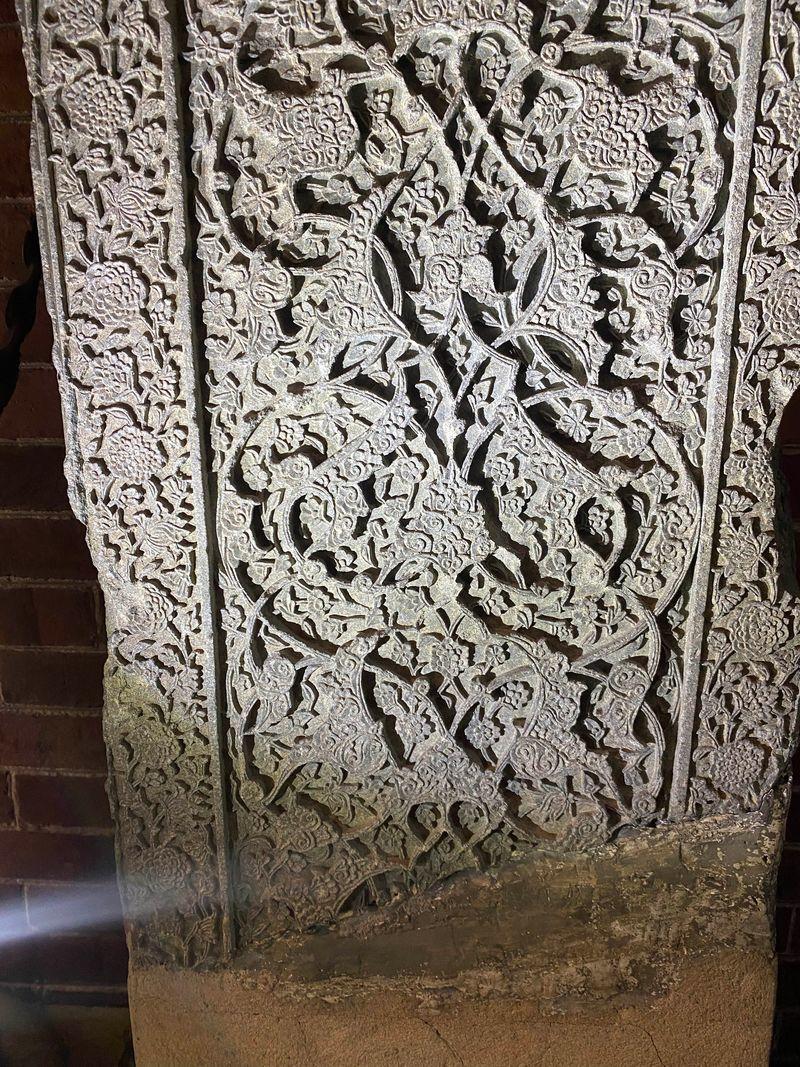

Close examination of the cenotaph in raking light reveals how expertly the sculptors carved the stone, which, based on elemental analysis and visual appearance, is likely schist. The detail below shows how they worked the material to fashion three distinct strata of decoration—the foundational ground, the intermediary plane, and the topmost level, which they rendered in highest relief. The multi-layered surface appears to interweave and billow as if it were in motion.

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston (S12w2). See it in the West Cloister.

Descriptive text: Persian, Herat (Afghanistan), Detail from Fragment of a Cenotaph in raking light, about 1475. Likely schist, 114.3 x 36.2 x 32.4 cm (45 x 14 1/4 x 12 3/4 in.)

The concept for this complex program of design likely originated on paper in a kitabkhana. Meaning “book house” in Persian, a kitabkhana combines the functions of both a library and a manuscript workshop. Timurid kitabkhanas additionally operated as clearinghouses for the production of designs on paper for translation into other media, including silk, wood, metal, and, indeed, stone. The drawings below contain designs that not coincidentally recall the cenotaph’s brilliantly worked surface.

The broad circulation of these designs on paper guaranteed that objects of various types and materials carried a common Timurid “look.” Take, for example, the designs on this late fifteenth-century wooden door panel from Samarqand, Uzbekistan, which in both concept and execution bear a resemblance to the cenotaph’s compositional program:

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (23.67.7)

Samarqand (Uzbekistan), Carved Door Panel, late 1400s. Cypress with traces of paint, 224.8 x 78.1 x 6.4 cm (88 ½ x 30 ¾ x 2 ½ in.)

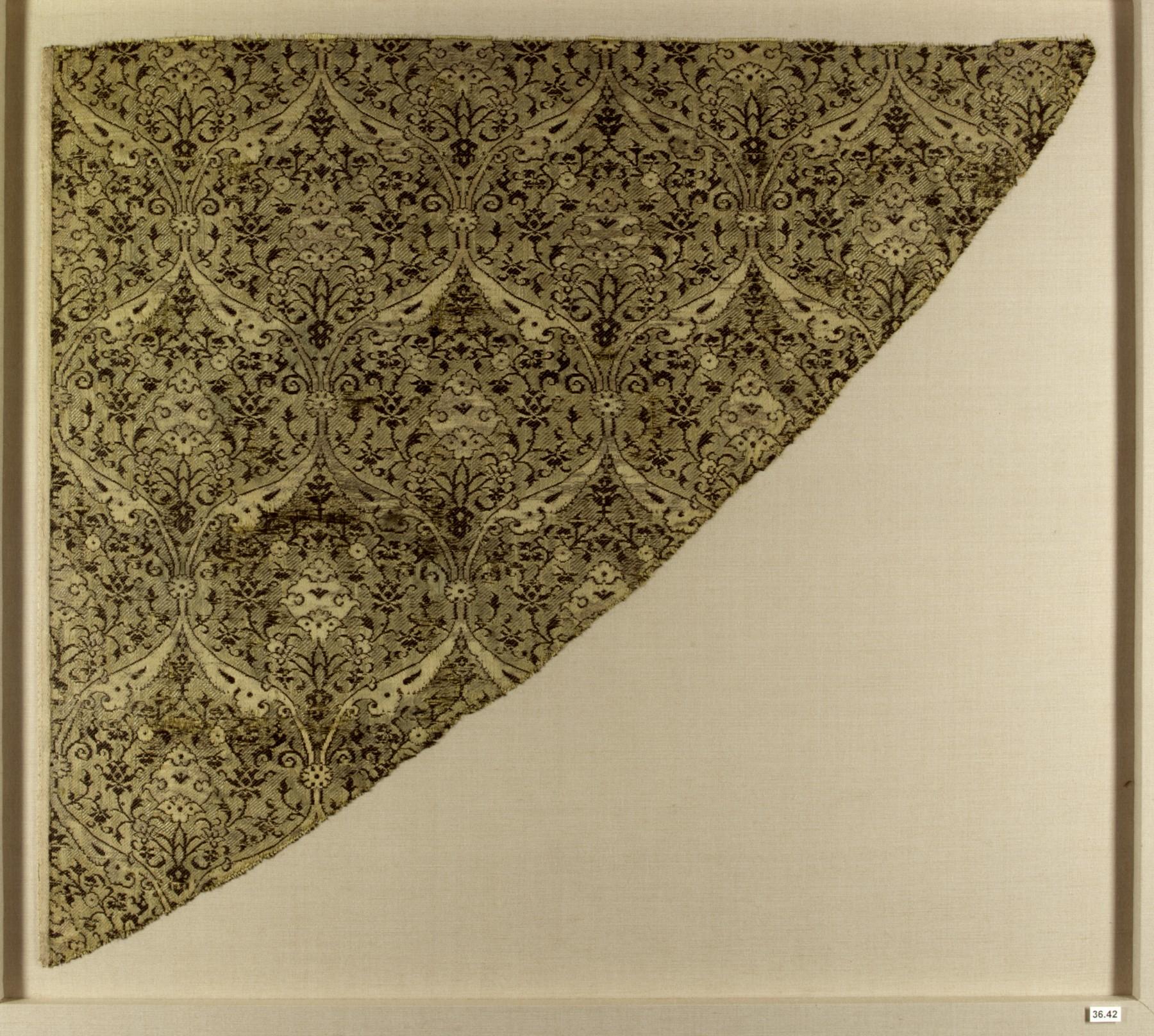

Or consider this similarly dated silk-woven textile, whose floral and geometric patterns similarly echo the cenotaph’s own:

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (36.42)

Descriptive text: Iran, Textile Fragment, late 1400s. Silk with metal-wrapped threads, 45.1 x 52.1 cm (17 ¾ x 20 ½ in.)

Working from a common pool of designs, Timurid artisans tweaked and embellished these schemas to suit the functions of the objects they crafted. On one end of the cenotaph, for instance, the sculptors carved the inscription al-hakim lillah (“judgment belongs to God”), an apt addition given the stone’s funerary context.

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston (S12w2). See it in the West Cloister. Alt text:

Persian, Herat (Afghanistan), Detail from Fragment of a Cenotaph in raking light, about 1475. Likely schist, 114.3 x 36.2 x 32.4 cm (45 x 14 1/4 x 12 3/4 in.)

As a passionate collector of objects made from a diverse range of materials, Isabella probably would have appreciated the stone cenotaph’s crossover connection with textiles, carved wood, and other media. She may very well have intuited these associations. In 1895, she acquired a sixteenth-century silk velvet panel from Iran that shares the bilateral symmetry, imaginative interweaving of vegetal and floral motifs, and overall compositional logic of the cenotaph, which she would purchase just six years later.

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston (T26n2). See it in the Titian Room.

Iran, Furnishing or Garment Fabric, late 1400s or early 1500s. Silk and foil-wrapped silk velvet , 57.2 x 33 cm (22 1/2 x 13 in.)

If Isabella indeed recognized these visual correspondences, she nevertheless chose to display the two objects in different locations. The velvet lives in the Titian Room, two flights of stairs away from the cenotaph.

You May Also Like

Read More on the Blog

A Rare and Unique Turkish Tile

Read More on the Blog

Three Chinese Islamic Altar Vessels

Read More on the Blog

Anna Hyatt Huntington’s World War I Memorial to the Sons of Gloucester

Learn More with the Recommended Reading

Yolande Crowe, “Some Timurid Designs and their Far Eastern Connections,” in Timurid Art and Culture: Iran and Central Asia in the Fifteenth Century, edited by Lisa Golombek and Maria Subtelny (Leiden: Brill, 1992), 168–178.

Helmut von Erffa, “A Tombstone of the Timurid Period in the Gardner Museum of Boston,” Ars Islamica 11/12 (1946): 184–190.

Lisa Golombek, The Timurid Shrine at Gazur Gah (Toronto: Royal Ontario Museum, 1969).

Thomas W. Lentz and Glenn D. Lowry, Timur and the Princely Vision: Persian Art and Culture in the Fifteenth Century (Los Angeles: Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 1989).

David J. Roxburgh, “Persian Drawing, ca. 1400–1450: Materials and Creative Procedures,” Muqarnas 19, no. 1 (2002): 44–77.

1Reproduced in Helmut von Erffa, “A Tombstone of the Timurid Period in the Gardner Museum of Boston,” Ars Islamica 11/12 (1946)184-190, 184.