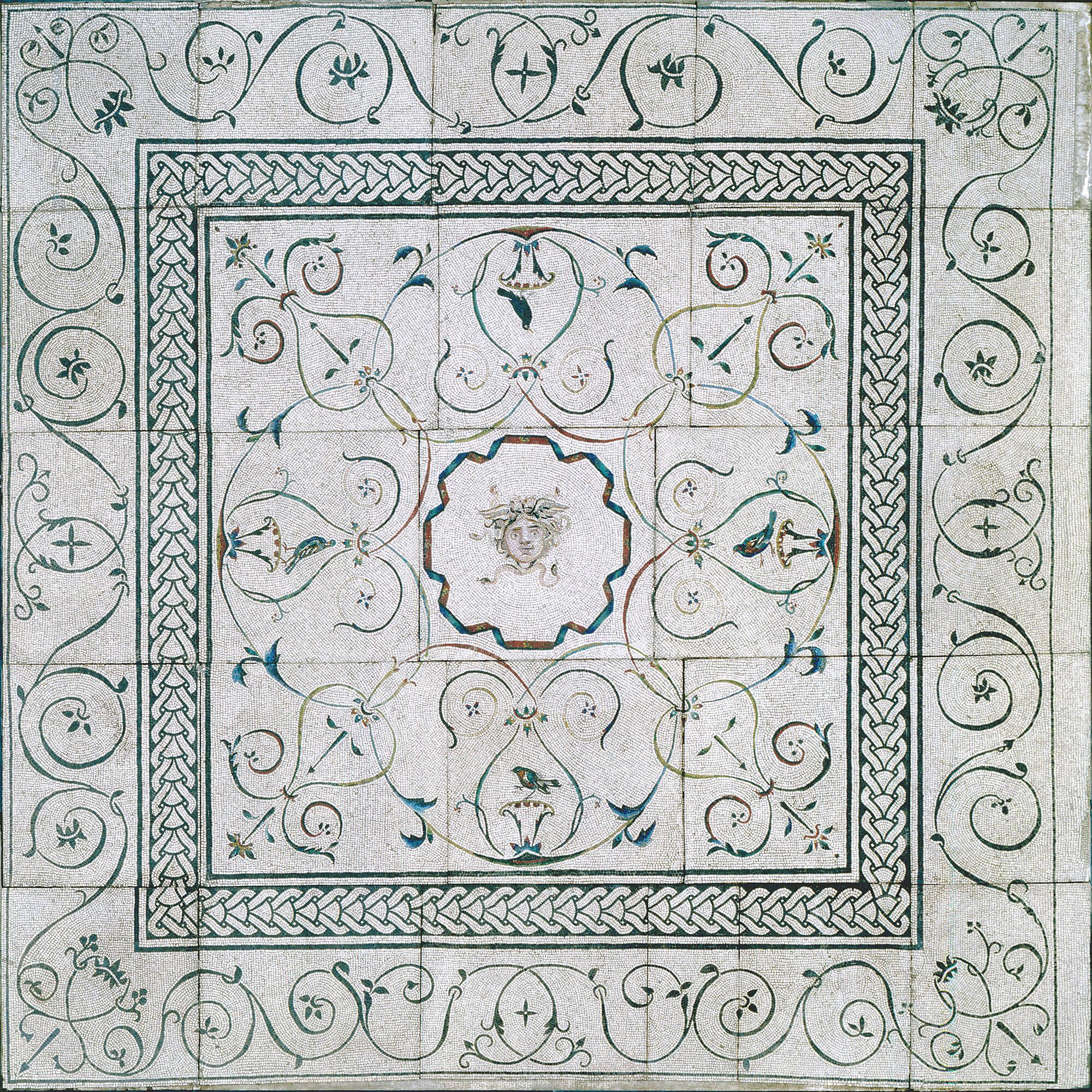

Imagine: you’ve been invited for a weekend visit to a villa in Prima Porta, a bucolic spot about eight miles north of Rome made fashionable by the Emperor Augustus and his wife Livia who retreated there to escape the heat and politics of Rome. You have the run of the estate, including the private bath facilities. You enter the baths through a large room, walking across a floor made of cubes (tesserae) of stone and glass laid in a design of delicate vine tendrils with birds perched upon floral blooms. The design is one more often used in more vertical displays, such as in four-part vaulted ceilings to show a vine arbor overhead. But even underfoot this tranquil Roman décor brings nature inside to simulate a garden in perpetual bloom. And then suddenly the peaceful atmosphere is disrupted by the representation at the center—a disembodied head with snakes in its hair and coiled around its neck. This disconcerting creature strikes a strident chord in a picturesque scene.

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston

Roman, Mosaic Floor: Medusa, 117-138 AD. Stone and glass, 500.4 x 1258.1 cm (197 x 495 5/16 in.)

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston

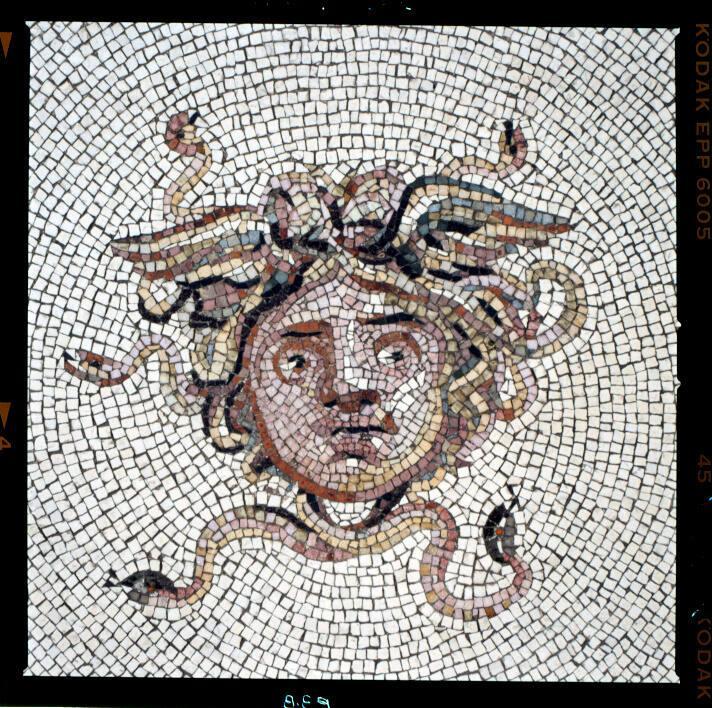

Roman, Mosaic Floor: Medusa (detail), 117-138 AD. Stone and glass, 500.4 x 1258.1 cm (197 x 495 5/16 in.)

Why the monstrous image here? Any habitué of wealthy Roman homes and baths knows that this head represents the Medusa. She protects the household against anyone wishing them ill. Even though ancient Greeks and Romans were gracious and hospitable, they were also generally known to be suspicious and fearful of those who might resent their success and wish them ill. Protective images (apotropaic symbols) such as the evil eye survive to this day as design elements in Mediterranean architecture, and in ancient times were placed at the entrances to homes and public spaces.

It comes as no surprise that Isabella would make sure this detail was included among the Roman, Byzantine, Romanesque, Gothic, and Renaissance elements of her Courtyard.

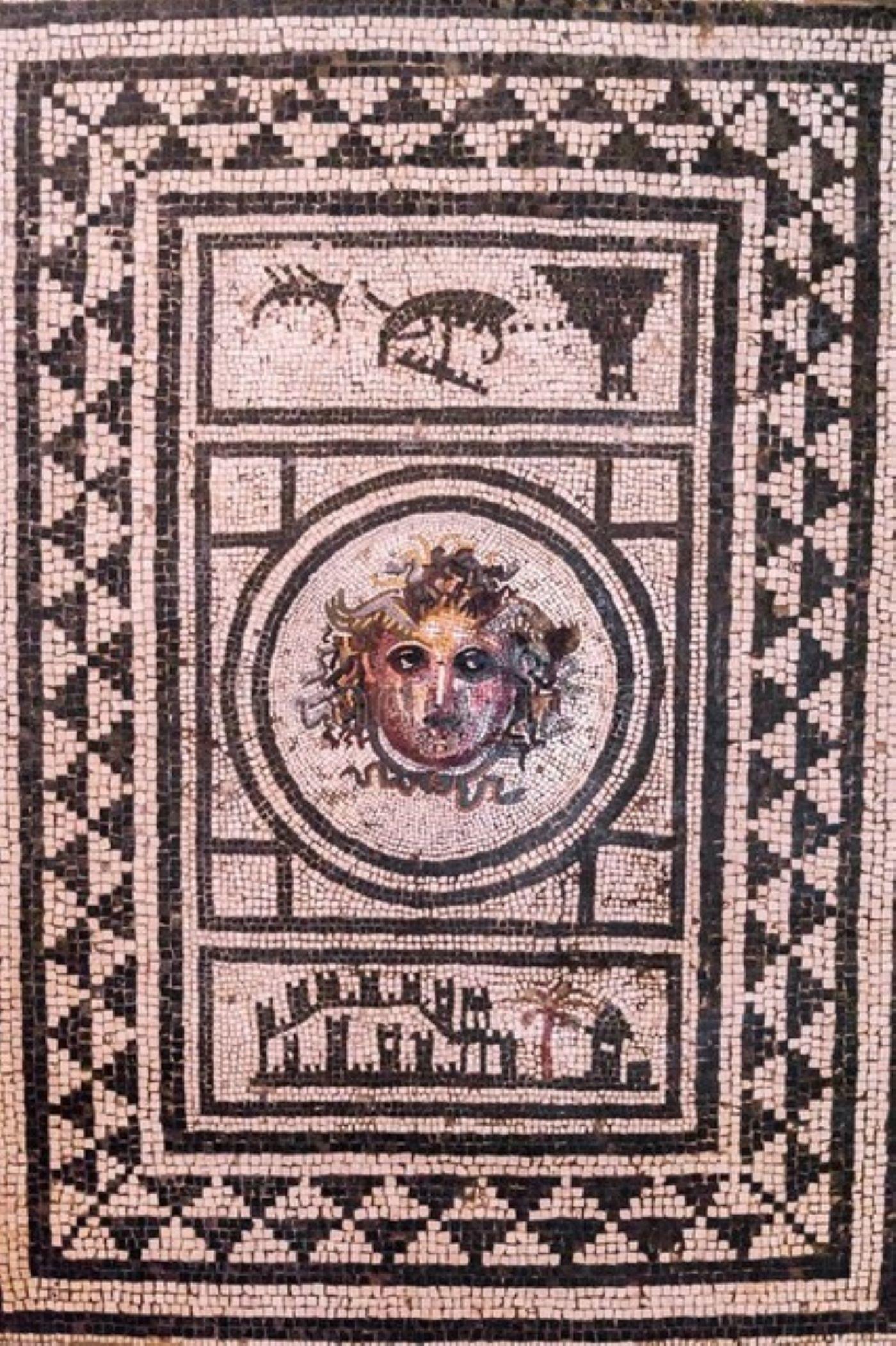

Museo Archeologico Nazionale di Napoli

Mosaic with head of Medusa from the House of the Vestals in Pompeii. Medusa as a protective device at the entrance to a house. You can see the port with ships (top) and the walled city (bottom).

Princeton University Art Museum (y1965-212). Gift of the Committee for the Excavation of Antioch to Princeton University

Roman, Mosaic pavement: head of Medusa, late 2nd century A.D. Stone, 331.0 x 197.4 cm (130 5/16 x 77 11/16 in.)

Archeological Museum of Sousse. © Ad Meskens / Wikimedia Commons. Mosaic floor depicting Medusa from a bath complex at Dar Zmela.

Roman, Tepidarium of Dar Zmela house, second half of the 2nd century

The Myth of Medusa: From Verminous Villain to Ghastly Guardian

But just how did the Medusa come to represent protection? Her story starts back in Greece and is recorded first by Hesiod in the sixth century B.C.E. in his poem “The Shield of Herakles.” In this epic story, a man named Perseus is tricked into accepting an impossible challenge, namely, to kill the Gorgon Medusa, a monster who turns people to stone with one glance. Perseus is offered divine assistance and props to accomplish the unthinkable.

When he reaches the land of monsters, he must use his human ingenuity to accomplish his goal. Stealing a single eye and tooth shared by three witch-like sisters, he forces them to tell him how to get to the ends of the earth where the Gorgons live. They give Perseus winged sandals to get there, a cap of invisibility to trick the Gorgons, and a magic bag in which to put the petrifying head of Medusa. Conveniently finding the monstrous Gorgons asleep, Perseus makes a surprise attack and chops off Medusa’s head guided only by the reflection in his polished shield.

On his action-packed winged journey home, he often needs to take the severed head out of the magic bag to turn his enemies to stone. When he reaches home, Perseus finds his mother Danae in the grips of an aggressive suitor, King Polydektes of Seriphos, whom he promptly petrifies using Medusa’s head.

Metropolitan Museum of Art (42.11.33). Samuel D. Lee Fund, 1942

Greek (Attic), Fragment of a relief with Achilles carrying a Gorgon shield, ca. 600 b.c. Terracotta, 16½ x 9⅞ x 1½ in. (42 x 25 x 3.7 cm).

Finally, Perseus delivers the prized powerful head to the warrior goddess Athena, who from that time on wears it on her breastplate to frighten her enemies. We know that the great Greek sculptor Pheidias featured the Gorgon in the shield as part of his colossal statue of the goddess inside the Parthenon. It was then the power of Medusa was immortalized.

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston (1980.196). Classical Department Exchange Fund. Statue of Athena that shows the Gorgon Medusa at the center of the warrior goddess’s breastplate.

Roman, Statue of Athena Parthenos (the Virgin Goddess), 2nd or 3rd century A.D. Marble from Mt. Pentelikon near Athens, 154 cm, 232.7 kg (60 5/8 in., 513 lb.)

Medusa Motifs

The myth of the Medusa remained popular for Greek and Roman artists and writers into the Renaissance age and beyond. Interpretations of Medusa in art allows for creativity, especially with eyes, the power of the gaze, the concepts of reflection and seeing, and the vital power of vision/representation. Medusa herself was a sculptor by default, but it’s ultimately her perilous artistry that conveys the power of protection.

Protection is the sentiment that is captured in the mosaic on the floor in the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum Courtyard. Museum visitors can find Medusa’s head placed within an octagon formed by a crinkled ribbon in the middle of the 16’ square-foot floor, surrounded by perpetually blooming, stunning horticulture.

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston. Photo: Sean Dungan

The Courtyard at the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum showing the mosaic.

Read More on the Blog

Attending to Women in Titian’s Mythologies

Gift at the Gardner

Full Medusa Mosaic Trivet

Read More on the Blog

From Venice to the Fenway: Architectural Elements in the Courtyard