The portrait of Eugénie-Désirée Fournier Manet (1811–1885), the artist Édouard Manet’s mother, has long held court in the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum. It entered the collection in 1910 and remained in the galleries for over a century. Excluded from major Manet exhibitions and their catalogues, the painting was understudied from a scholarly and technical perspective until the exhibition and publication Manet: A Model Family in 2024. In 2022, it received a transformative cleaning that revealed a virtuosity long obscured by a badly discolored and inappropriately shiny varnish.

The brushwork throughout most of the painting is beautifully bold. It shows confidence and dynamism that speaks to a certain speed of working that was not always typical of Manet. Some of his subjects recounted that they often had many long sittings. Nonetheless, he was occasionally capable of producing work in one session. His close friend Antonin Proust, whom Manet painted in 1880, reported that after many false starts and “using up seven or eight canvases, the portrait came all together at once. Only the hands and parts of the background needed to be finished.”

Toledo Museum of Art. Gift of Edward Drummond Libbey (1925.108)

Édouard Manet (French, 1832–1883), Antonin Proust, 1880. Oil on canvas, 129.5 x 95.9 cm (51 x 37 3/4 in.)

Looking at the surface of the portrait of his mother, there is evidence of similar speed and confidence in the final execution. A thick impasto in passages around the hair indicates Manet was handling a large amount of paint on the brush to capture the texture of his mother’s hair. The artist left ample evidence of his brushwork in the swirls and swathes of black-on-black in the dress and by allowing furrows to form in places like the hands, where he likely used a stiff hog-hair brush to impart extra texture to the paint surface.

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston (P3s4). See it in the special exhibition “Manet: A Model Family,” on view in Hostetter Gallery, October 10, 2024–January 20, 2025 or in the Blue Room.

Édouard Manet (French, 1832–1883), Madame Auguste Manet, about 1866, detail the hands holding a pair of handheld eye glasses, during the 2022 cleaning

The bold brushwork hides evidence of the significant revisions Manet made to the composition, namely the repainting of the sitter’s face and hands. In the lower portion of the painting, the earlier position of the hands, dress sleeves, and skirt is visible through the thin, finished layers of the black dress. The x-radiograph more clearly shows the considerable shifts in this area of the composition. Most notable of these changes is the repositioning of the hands, which initially were placed somewhat higher on the canvas, and with the proper left hand lightly grasping the fingers of the right hand. In the final version, the hands are placed slightly apart and hold an object, probably a lorgnon—a pair of handheld eyeglasses.

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston (P3s4). See it in the special exhibition “Manet: A Model Family,” on view in Hostetter Gallery, October 10, 2024–January 20, 2025 or in the Blue Room.

X-ray of Édouard Manet’s Madame Auguste Manet, about 1866, overlaid with the visible light image, showing the reposition of the hands

Though less evident in the x-ray, Madame Manet’s face also underwent considerable reworking, revealed by the removal of the dark veil of yellowed varnish. Manet did not entirely cover the earlier version of the face. In portions of the forehead, most notably along the right side, brush marks of the pale yellow paint that made up the first version of the face are still visible through the cooler, pink pigments that define the final version.

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston (P3s4). See it in the special exhibition “Manet: A Model Family,” on view in Hostetter Gallery, October 10, 2024–January 20, 2025 or in the Blue Room.

Édouard Manet (French, 1832–1883), Madame Auguste Manet, about 1866, detail showing the thick paint of the hair

Traditionally, the painting has been dated to around 1863. However, in Manet by Himself (1991), Juliet Wilson-Bareau applied a date range of 1863 to 1866. The start date of 1863, based on Eugénie’s mourning dress, worn after the death of her husband Auguste, is appropriate. Madame Manet’s black dress and jewelry identify a start date but not an end date; she wore widow’s black for the rest of her life. Archival evidence suggests the painting was finished—and maybe started—as late as 1866.

The author and friend of Manet’s, Émile Zola wrote in his 1867 biography of Manet that in 1866 the paint was “just dry” on four works including “Portrait de Mme M . . .” From titles and descriptions, three of the paintings are identifiable, but the title Portrait de Mme M . . . is ambiguous. By 1866 there were two Madame Manets in the artist’s life: his mother and his wife. In a 1907 issue of the obscure publication Le Journal des curieux, an author named André Chatté states, after quoting Zola’s praise, that the portrait of Mme M … is one of the artist’s best works:

The portrait of Madame Manet mère shows her seated in a natural, familiar pose, holding her lorgnette [handheld eyeglasses] in both hands; the background of the painting is black, and she is completely dressed in black. . . . Her hair is arranged in the fashion of the 1830s, which she has kept all her life. . . . The pleats adorning her sleeves, the ribbon of her belt, and the buckle are visible, although everything is black. The figure is energetic, with an expressive gaze that follows you wherever you go. . . . [Her] features reveal . . . a firm and authoritative character.

Clearly, Chatté knew, or thought he knew, that “Mme M” referenced by Zola as a work completed in 1866 was, in fact, the portrait of the artist’s mother rather than an image of Suzanne Manet.

Apart from his writing at a relatively early date, why should one take Chatté’s word for this identification? Perhaps because Chatté (who has no other known bylines in the French press) may be Léon Leenhoff, Suzanne Manet’s son and Édouard’s godson, writing under a pseudonym. Leenhoff, whose mother had died the year before, was now responsible for the disposition of Édouard Manet’s works that had remained in his and Suzanne’s possession. Among them was Madame Auguste Manet, which Léon sold to a London dealer in 1909 for 90,000 francs—equivalent to about 600,000 dollars today.

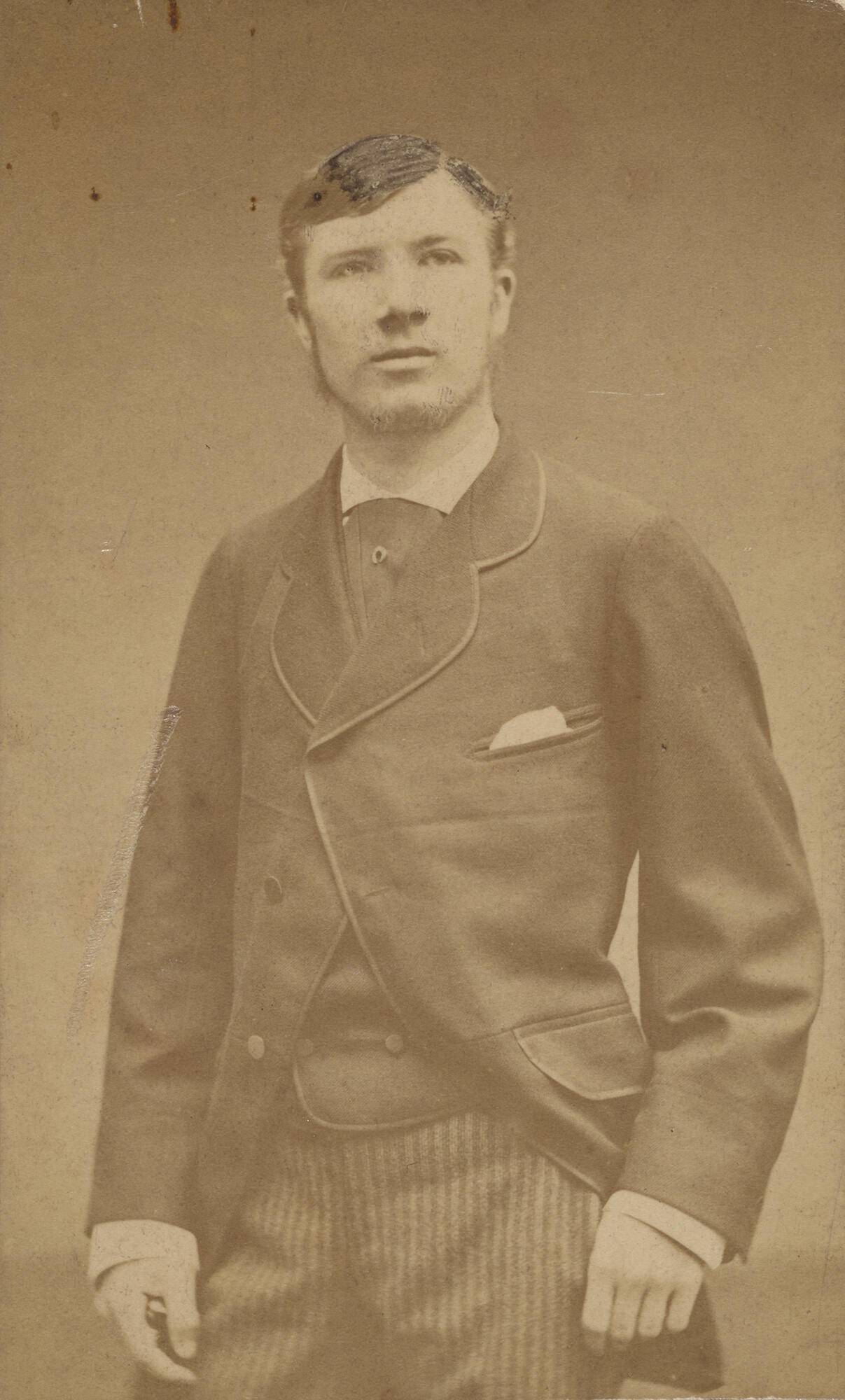

The Morgan Library & Museum, New York (MA 3950). Purchased as the gift of Mrs. Charles Engelhard and children in memory of Mr. Charles Engelhard, 1974

Unidentified photographer, Léon Leenhoff, 19th century. Care-de-visite, 9.2 x 5.6 cm (3 ⅝ x 2 ¼ in.)

Chatté—probably Leenhoff—also specifically references two Old Master painters related to the painting: Frans Hals and Francisco Goya. In the fall of 1863, after marrying Suzanne, Manet spent a full month in the Netherlands, likely immersed in Dutch art, including Hals’s paintings of older women in black. Two years later, in 1865, he traveled to Spain, where he saw many more works by Spanish masters at the Museo del Prado, such as Goya and Diego Velázquez.

Madame Auguste Manet combines details that feel Dutch and Spanish. The restrained palette is reminiscent of Velázquez. The pose and depiction of a powerful older woman in black recall Dutch portraits like Hals’s Maritge Claesdr. Vooght. The black lace head covering almost resembles a mantilla, harkening to Goya’s Majas on a Balcony. Muting the colors of his mother’s face to shift from rosy pink to cooler pale white suggests a change—perhaps—from a Hals-like image of flushed cheeks to a more restrained skin tone.

Therefore, Manet likely started this painting after his extended 1863 wedding trip to the Netherlands and possibly after his excursion to the Iberian peninsula from August to September 1865. That trip was immediately followed by a vacation with his family—including his mother—in the French countryside. By October 1865 Manet was back in Paris, hard at work on a series of paintings, likely including Madame Auguste Manet, that would be finished by 1866.