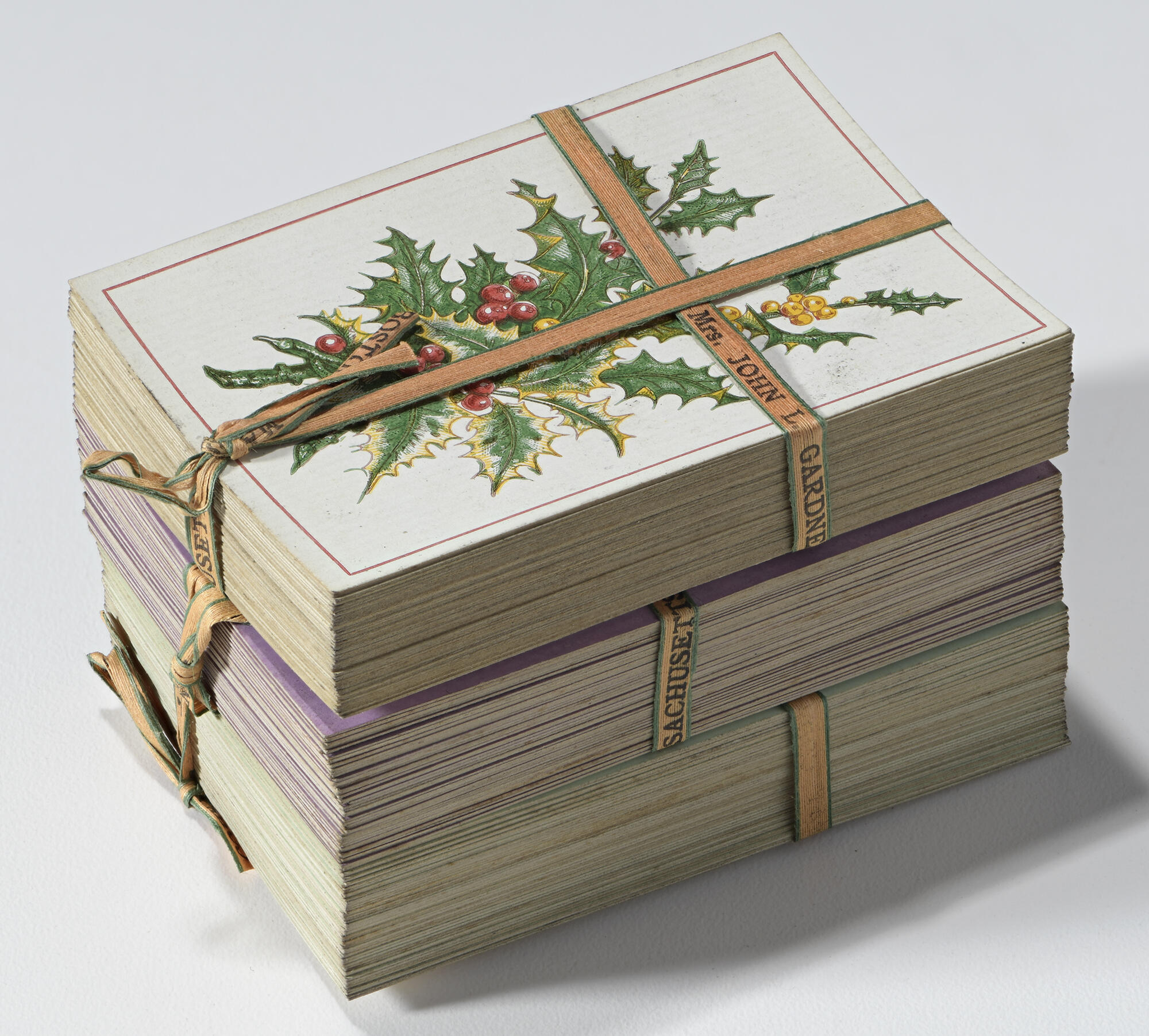

Isabella Stewart Gardner designed her museum to be an immersive experience born from her love of art, beauty, and travel. She curated multidimensional gallery spaces, where the depth of her collection extends beyond the paintings on the walls to an unseen trove of memorabilia and ephemera, tucked away in countless drawers, cabinets, and boxes. Among these hidden objects, Isabella included six decks of playing cards, which offer a peek into the museum founder’s playful, game-loving side.

I envy you, who always, even at your worst, loved the game, whatever it might be, and delighted in playing it.

— Henry Adams to Isabella Stewart Gardner, after 1906 (ARC.000019)

Isabella loved to travel and visited approximately 39 countries between 1867 and 1899. Similar to today, playing cards were an ideal source of entertainment for the 19th century traveler. Small and compact, they fit inside luggage without sacrificing the limited space. Isabella’s decks tell the story of a grand tour of Europe, with three standard 52-card packs from England, a 40-card deck celebrating famous matadors from Spain, and two sets used for divination from Italy.

The English Trick-Taking Decks

During the 19th century, two trick-taking card games reached the height of their popularity in England—whist and bezique. While whist required a standard 52-card deck for gameplay, the earliest versions of bezique only used 32 cards, later evolving into a multiple-deck game in the second half of the 19th century. By that point in time, the strictly defined gender roles for men and women, which existed elsewhere in society, were largely absent from playing card culture. Isabella and other women with similar standing in America and England were now encouraged to play and hone their skills.

© The Trustees of the British Museum (1935,0522.7.234)

Theodore Lane (British, 1800-1828), Whist. Pl. 1. A Rub, 1822. Ink on paper, 27.4 cm x 22.2 cm (10 ¾ x 8 ¾ in.)

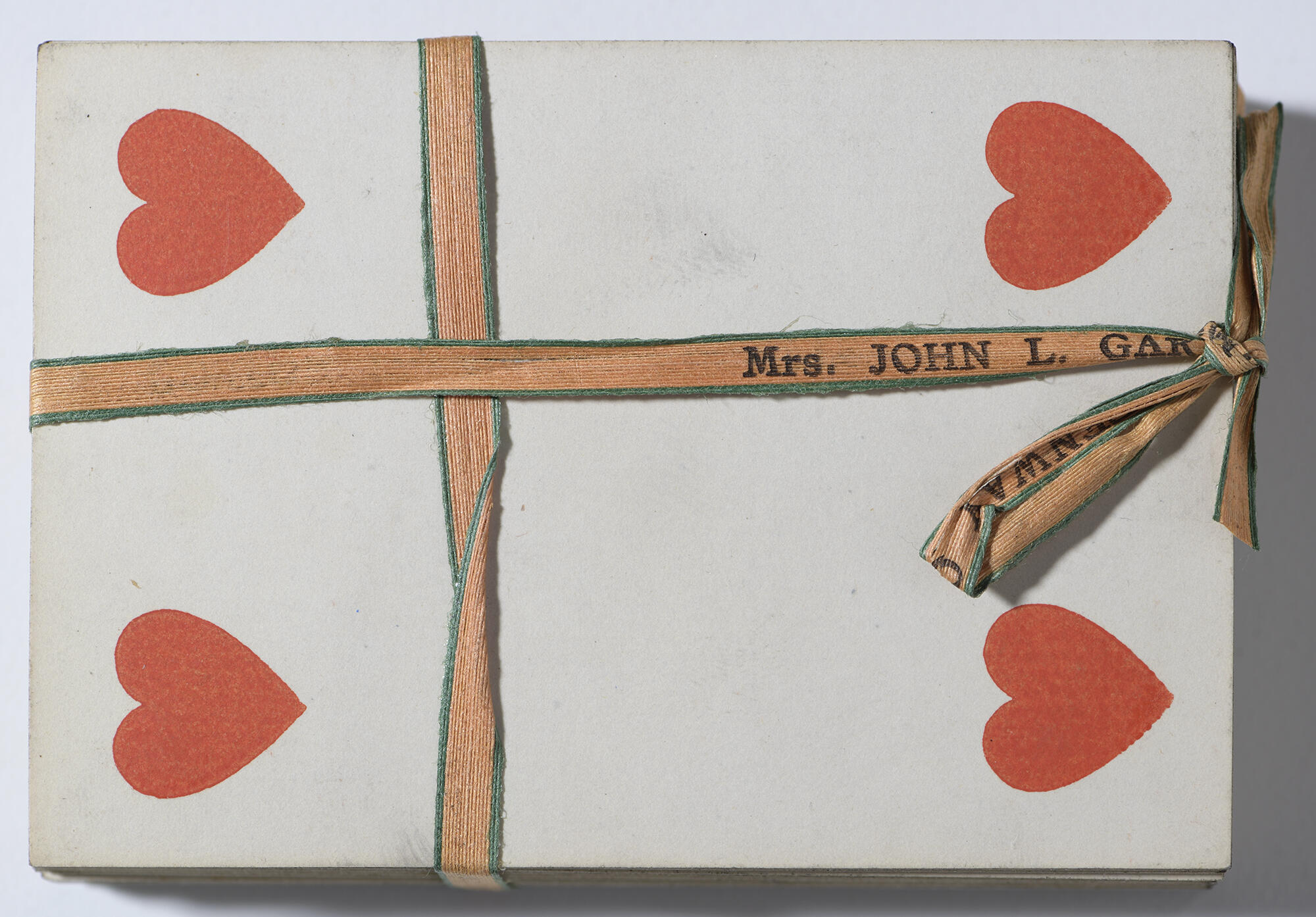

The three English decks from the Gardner collection were originally stored in a console table in the Macknight Room, alongside four score markers used for whist and bezique. The decks were manufactured by playing card maker Charles Goodall & Sons between 1865–1875 in London. Isabella traveled to England several times between 1879 and 1892 and likely acquired these decks on one of her trips abroad.

The score markers that were stored alongside the decks indicate that Isabella likely used the cards to play whist and bezique. While counters for scoring had been used since the early origins of whist, the late 19th century saw the advent of a more elegant scoring marker for the game. Following the lead of the whist marker, new designs for bezique markers also entered the English market in the 1880s.1

The markers in Isabella’s collection are unique, in that they do not wholly resemble the products that were being made by the largest British manufacturers of the time, such as Goodall and De La Rue. The two whist markers were specifically designed for a version of the game called ‘long whist,’ which was played to 10 points. This style of playing was overtaken in popularity in the mid-19th century by ‘short whist,’ which was played to 5 points. However, in the second half of the century, the top British manufacturers still created markers capable of scoring both versions of the game. Isabella’s markers do not have this capability which, in combination with their unusual design, suggests that they were likely made in America, where players preferred a version of short whist with a game requirement of 7 points.2

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston (U11n29.1-2)

Possibly American, Pair of Whist Markers, 19th century. Textile fibers with stamped gold leaf and metal, 4.6 x 4.6 cm (1 13/16 x 1 13/16 in.)

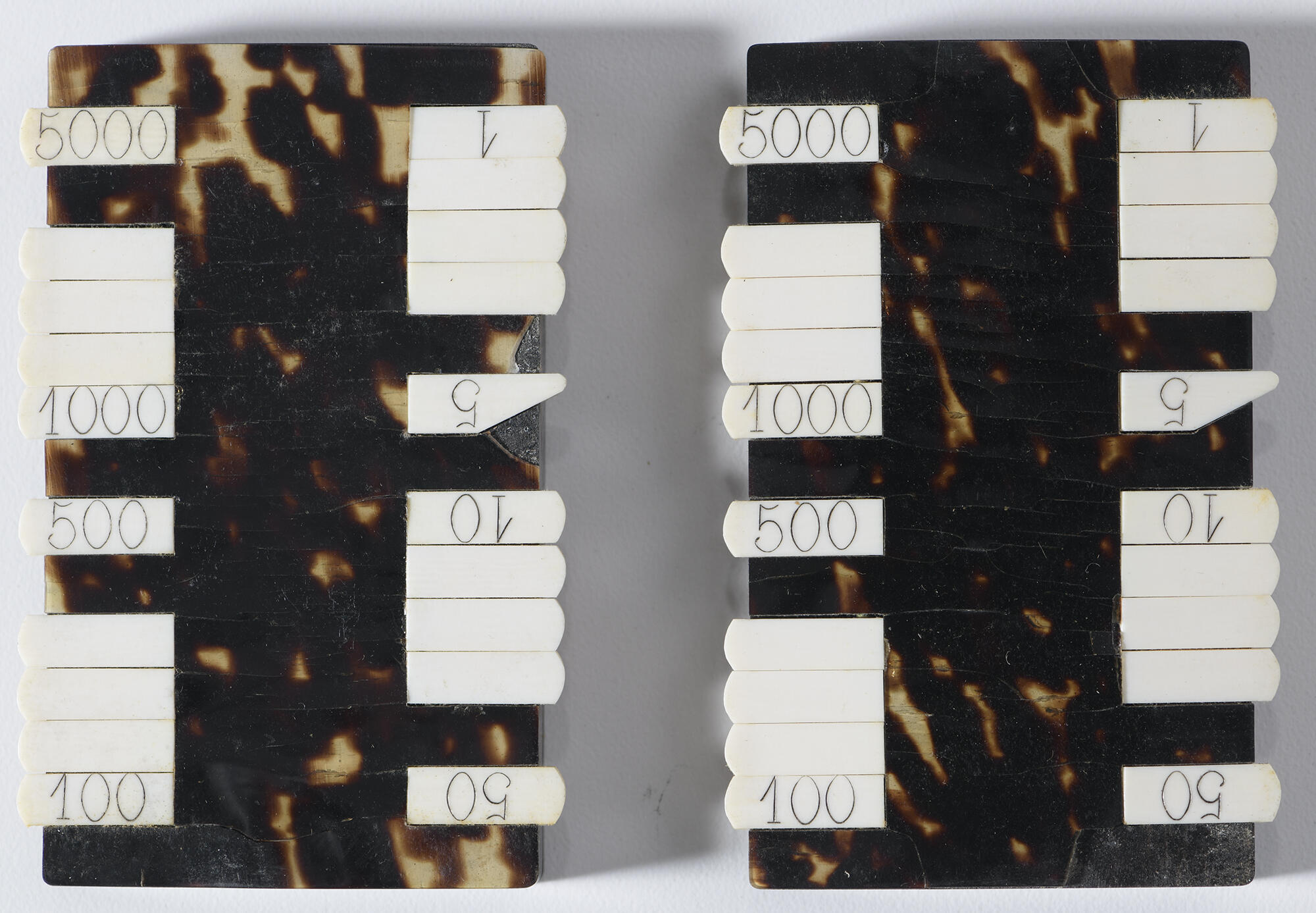

The bezique markers are similarly unlike 19th century examples available today. While they do sport Goodall’s ingenious ‘pop-up’ indicator design along the sides, the inexpensive, faux-tortoiseshell surface suggests they were likely made on the European continent for export.

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston (U11n33.1-2)

Possibly European, Pair of Bezique Markers, after 1880. Plastic and wood, 8.7 x 5.7 x 0.8 cm (3 7/16 x 2 1/4 x 5/16 in.)

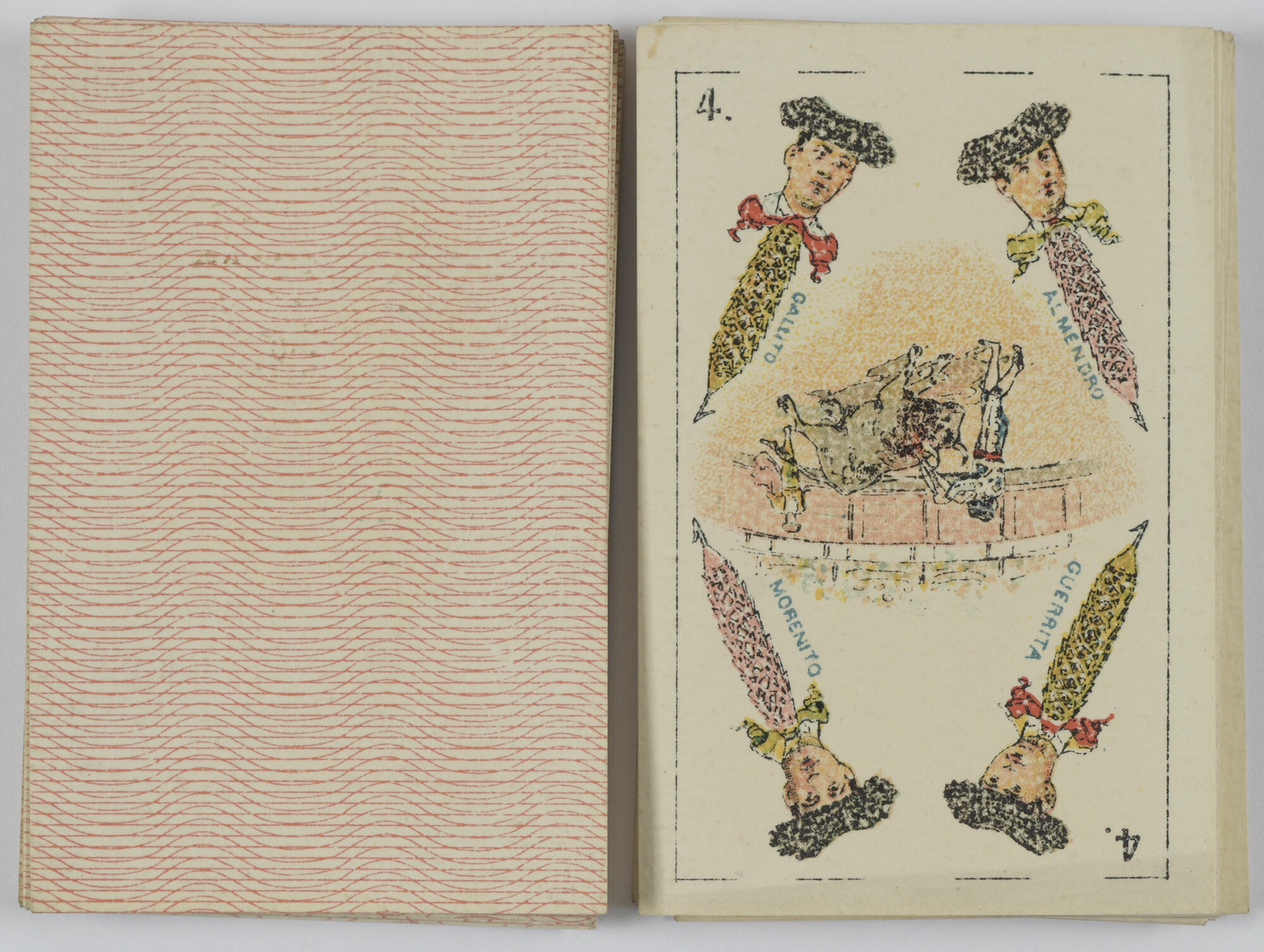

The Spanish Bullfighting Deck

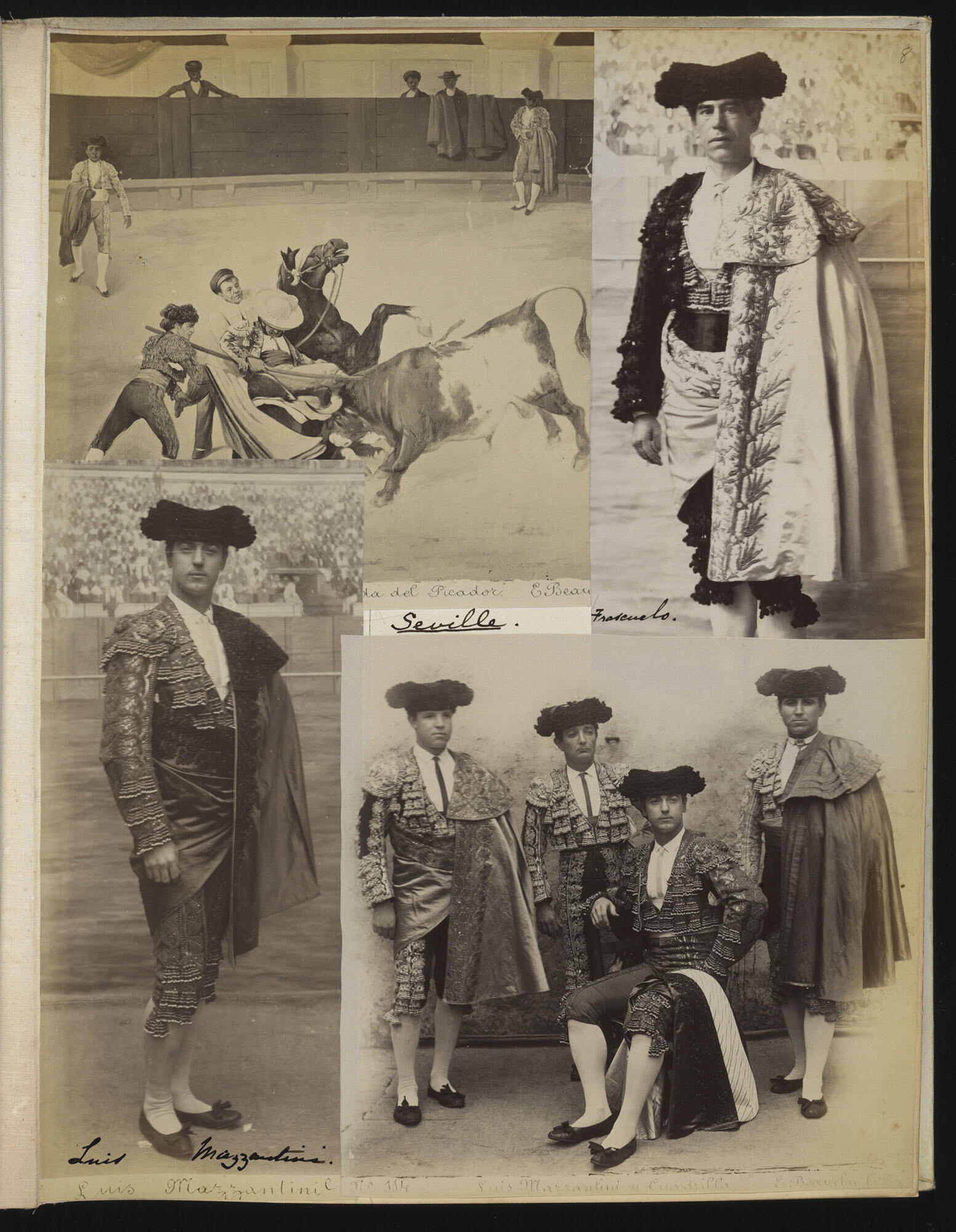

In 1888, Isabella and her husband Jack traveled to Spain and Portugal. The trip was recorded by Isabella in two travel albums (v.1.a.4.15 and v.1.a.4.16), which she filled with photographs, prints, and written accounts of their adventures. The couple spent part of March and April of that year in Seville, Spain, observing the celebrations for Semana Santa de Seville and attending the epitome of Spanish cultural events—bullfighting. As an outspoken animal lover, Isabella was horrified by the cruelty and “crouched on the floor and covered her eyes,” especially when famed matador Luis Mazzantini killed a bull in Isabella’s honor.3

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston (ARC.006510)

Spanish, Luis Mazzantini, about 1888. Albumen print on card, 10.5 x 7 cm (4 1/8 x 2 3/4 in.)

Although the fight wasn’t necessarily to Isabella’s tastes, she did collect a few souvenirs from the experience, including photographs of the matadors and a deck of playing cards, which she stored in a box on top of the desk in the Macknight Room. The deck was created by playing card maker Pedro Maldonado in Madrid around 1875–1885 and was known as the Nueva Baraja Taurina, or New Bullfighting Deck. It features Spanish-style suits, such as swords (espadas), cups (copas), and coins (oros). The clubs (bastos) are illustrated to look like banderillas, which were used in bullfighting to weaken the animal. Throughout the deck, the faces of famous matadors have been integrated into the pips, or suit symbols. The deck would have included 40 cards, which is common for a Spanish-suited deck, and was likely used for the game ombre. Only 25 cards remain in Isabella’s deck.

On the One and Two of Swords, two matadors, whose pictures are included in Isabella’s travel album, are represented. Can you spot them?

The Italian Divination Decks

Isabella traveled to Italy more than any other country and took inspiration from its rich culture when designing and filling her museum. Evidence of this can be seen in everything from the architectural elements framing the windows to the Renaissance masterpieces on the walls, and, on a smaller scale, two decks of divination cards that were tucked away on the desk in the Macknight Room and in a box in the Little Salon.

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston. Photo: Sean Dungan

Isabella’s Venetian-inspired Courtyard

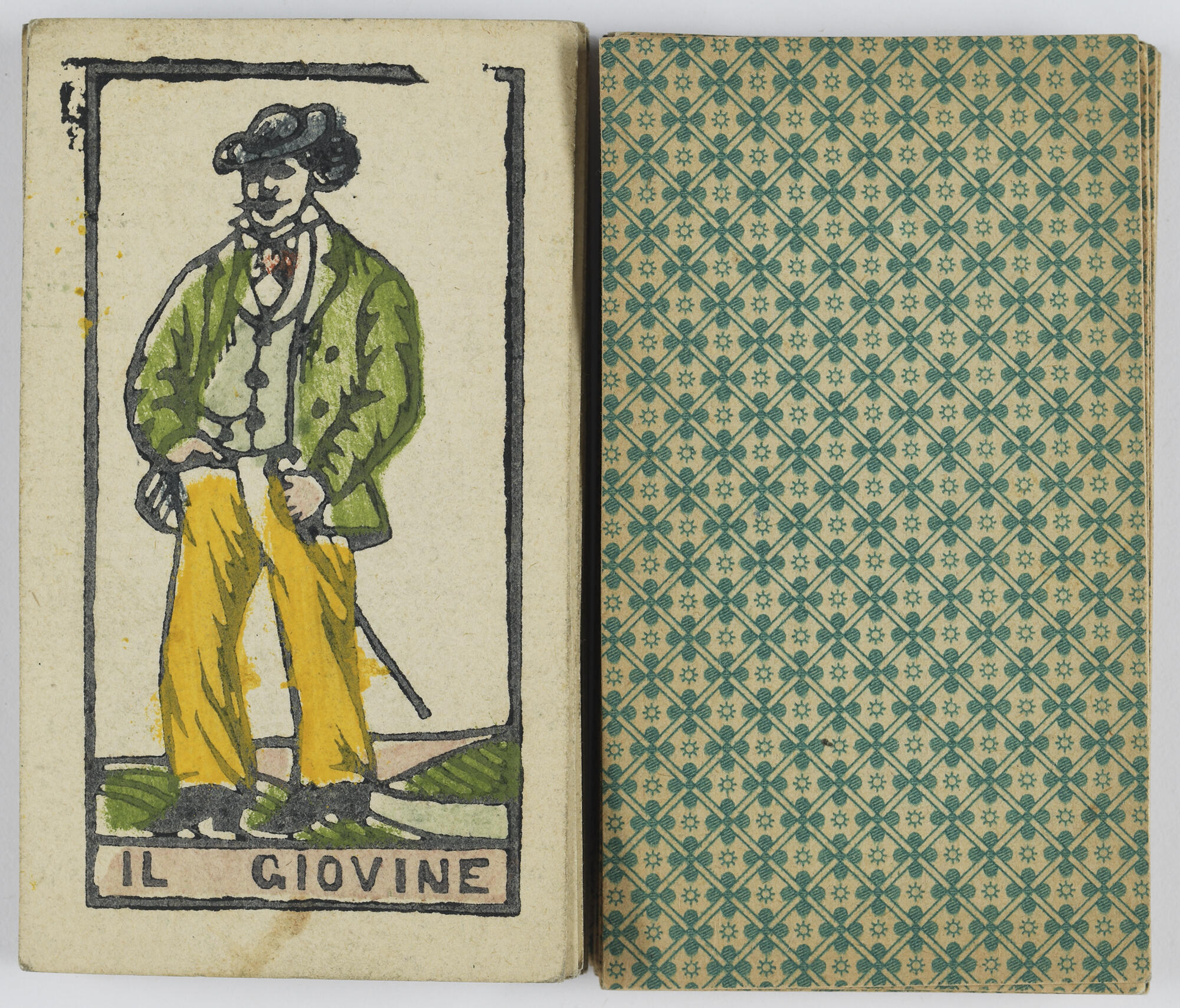

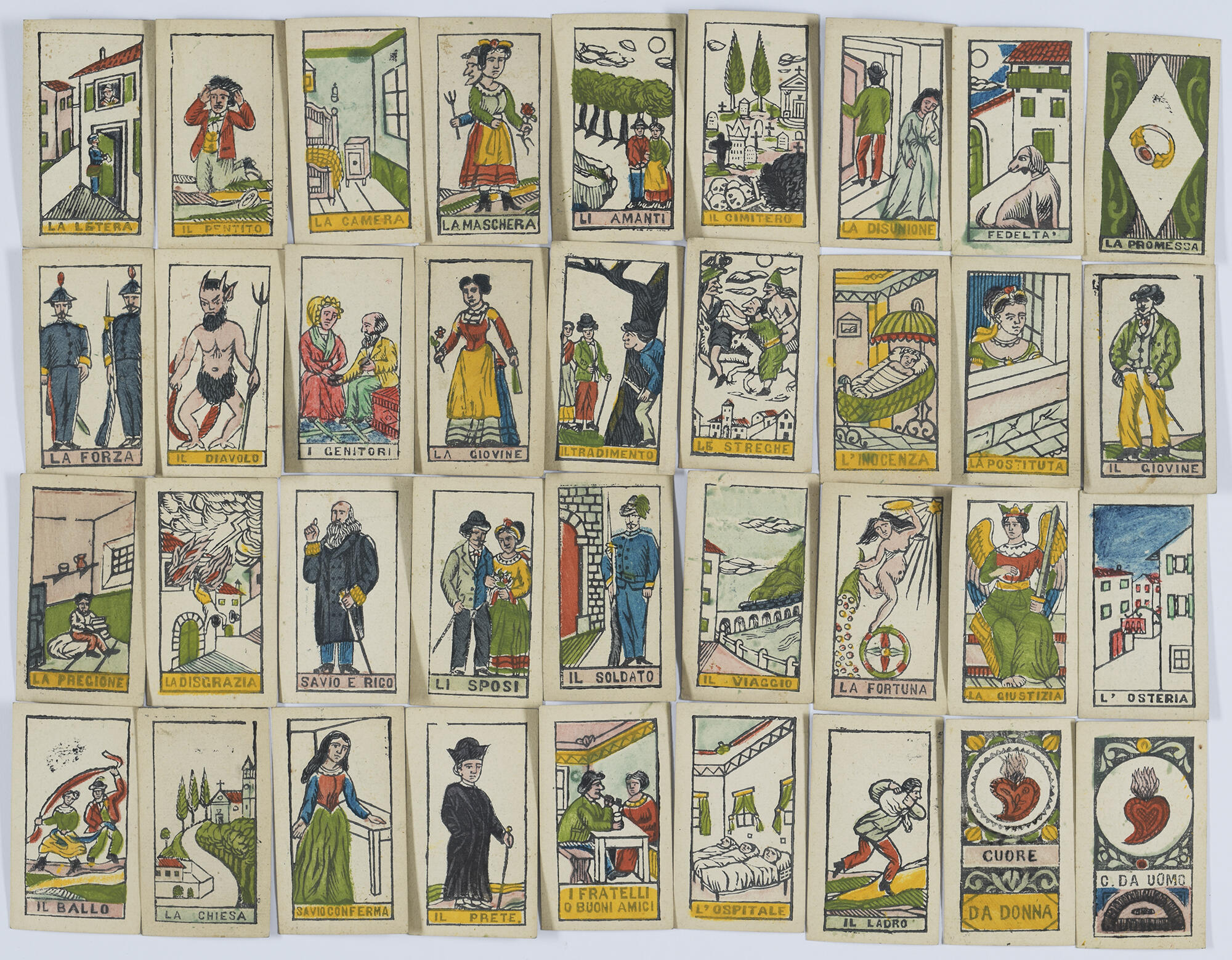

When it was originally inventoried after Isabella’s death, the deck from the Macknight Room was something of a mystery. It resembles a deck of tarot cards, although it only has 36 cards instead of the standard 78 (22 Major Arcana and 56 Minor Arcana). Another possibility is an Italian-inspired oracle deck, modeled on the 36 Lenormand cards—named after famed 18th century fortune-teller Marie Anne Lenormand. However, the true identity of this deck may be a bit more complex.

Comparing Isabella’s cards to other examples of cartomancy decks suggests that they are likely a version of the 36-card fortune telling decks used by the Romani people. Similarities between Isabella’s Italian deck and those from Germany and Austria in the 19th century arise in the types of cards and shared imagery, like a dog to depict ‘Faithfulness’ and a burning building to depict ‘Misfortune.’ A clear example of Italian cultural influence can be seen in cards like ‘Il Soldato.’ In the northern versions, it is known as ‘Officer,’ and represents a keeper of order. This deck uses a soldier in a distinct 19th century Italian military uniform, likely acknowledging the national role of their armed forces.

While this deck, and others like it, cannot be categorized as what is conventionally considered a ‘game,’ it is still part of an enduring tradition of cards being used as a way to bring people together through a shared cultural experience.

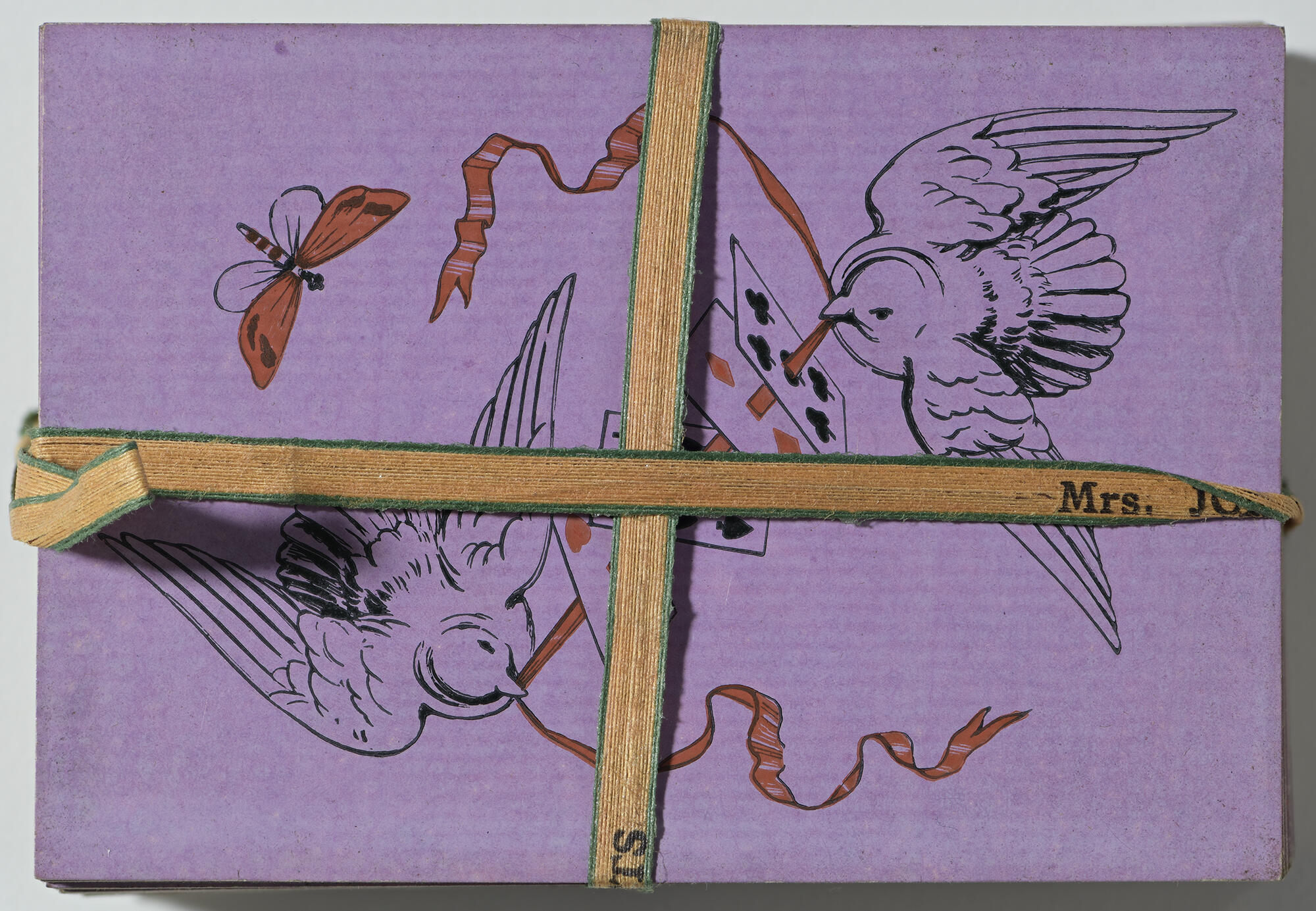

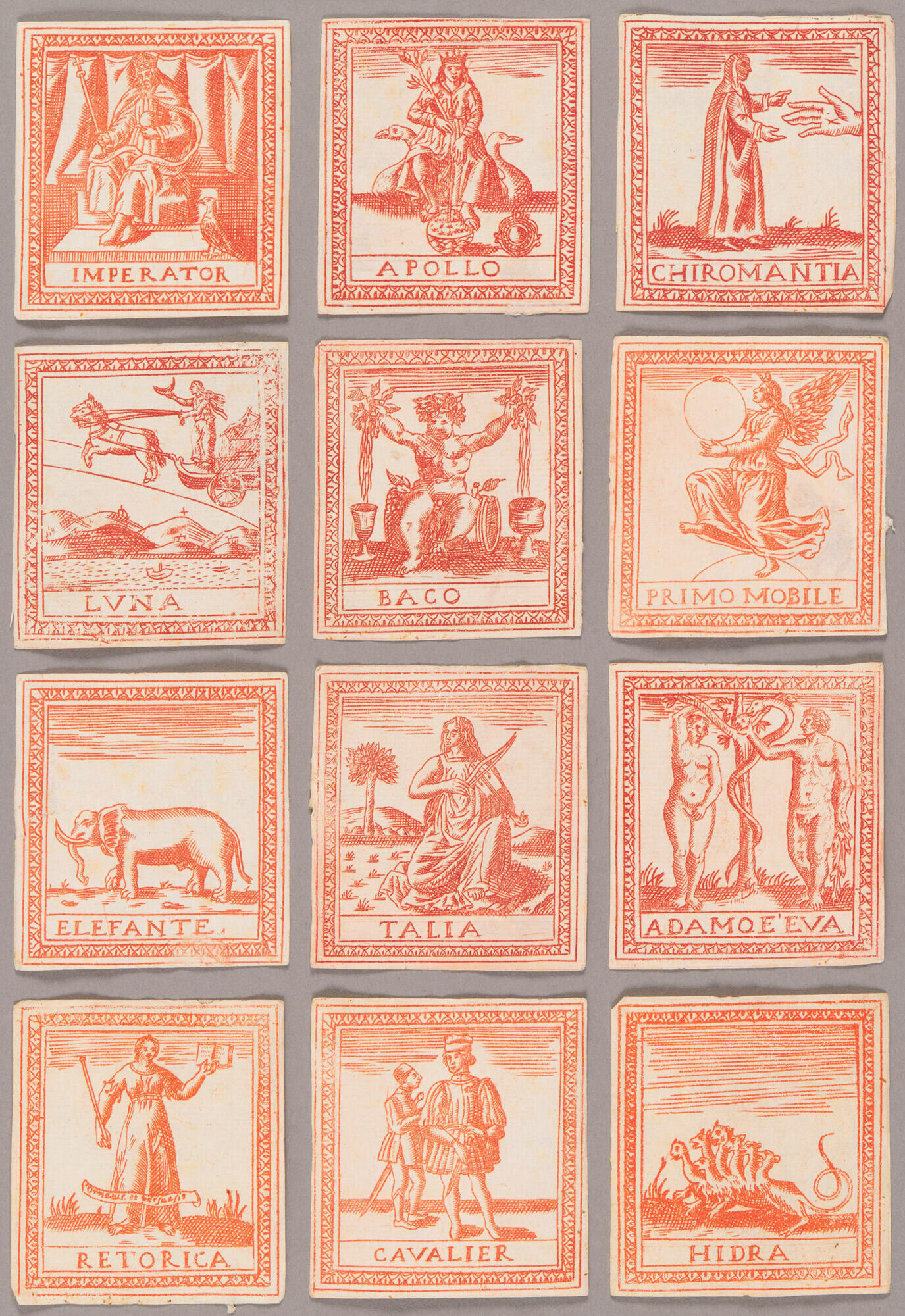

The second Italian deck in Isabella’s collection, originally stored in a box in the Little Salon, similarly does not appear as it seems at first glance. Resembling stamps more than standard playing cards, this deck was actually used as part of a 17th century ‘mind reading’ game called Laberinto (Labyrinth), created by Andrea Ghisi in Venice.

Played with 60 cards, whose designs were based on the so-called Mantegna Tarocchi, Laberinto was a game described by its creator as an “exercise in idleness.” A book published by Ghisi in 1607 offered directions on how to play his new game, which was meant to effectively ‘guess what any one was thinking.’ In reality, Laberinto was a pseudo-mind reading game, played by narrowing down subsets of cards. [You can play a version of the game online!]

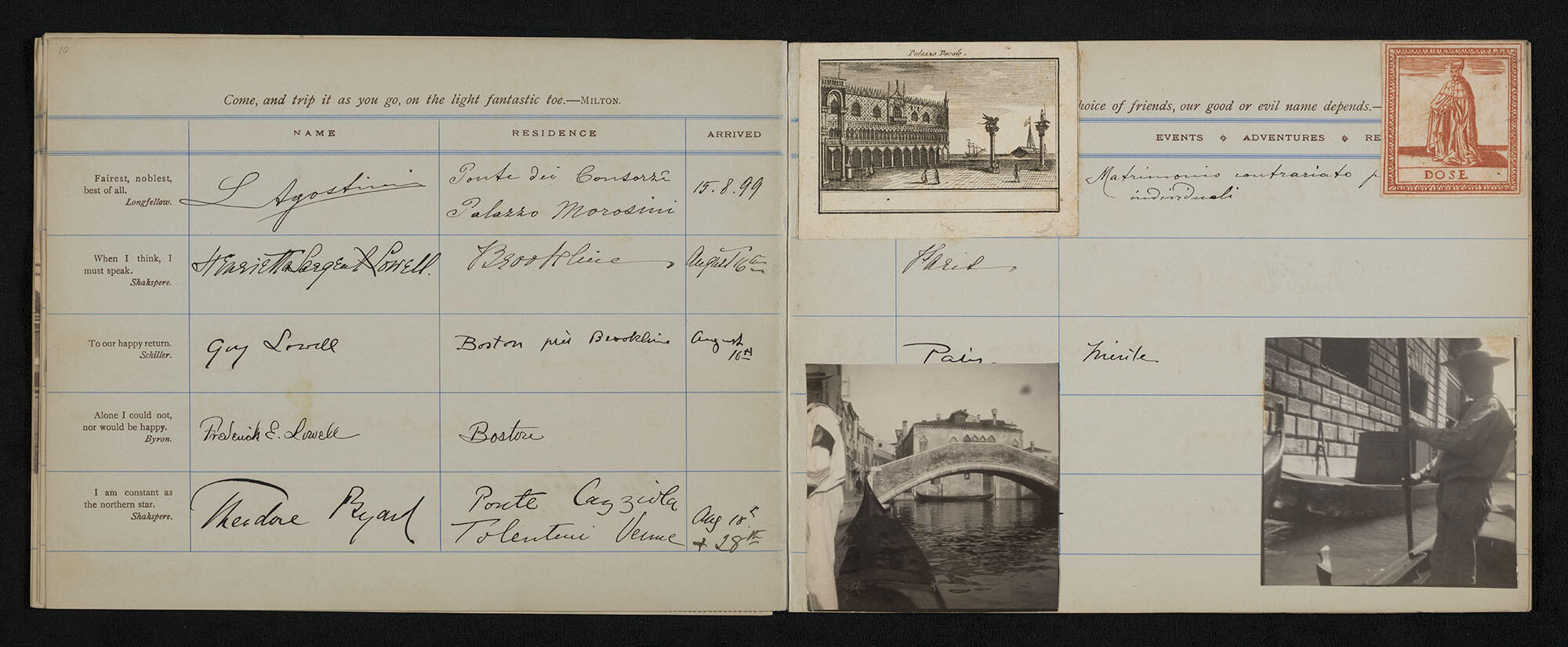

Isabella’s deck only contains 13 of the original 60 cards. 12 cards were stored in the Little Salon and a 13th card was pasted to a page inside one of Isabella’s guest books. Appropriately, the page records the names of those that visited her in August of 1899, while she was staying in Venice—the birthplace of Laberinto.

This selection of decks from the Gardner represent only a small part of the history of the playing card, which is over a thousand years in the making. However, Isabella’s inclusion of them in her collection helps to provide a lasting example of their multifaceted legacy—one that encompasses not only the evolution of design and function, but of participation, community, and culture.

I want to extend my sincerest gratitude to Ken Lodge and Tony Hall. Their combined knowledge, and that of all the other wonderful contributors at The World of Playing Cards, was paramount to writing this blog. Thank you for helping to enrich our collection.

1Tony Hall. “Bezique Markers, 1860-1960,” The World of Playing Cards, 9 July 2023, www.wopc.co.uk/members/tony-hall/bezique-markers-1860-1960

2Julian Laderman. Bumblepuppy Days: The Evolution of Whist to Bridge (Toronto, 2014).

3Morris Carter. Isabella Stewart Gardner and Fenway Court (Boston, 1925), p. 106.