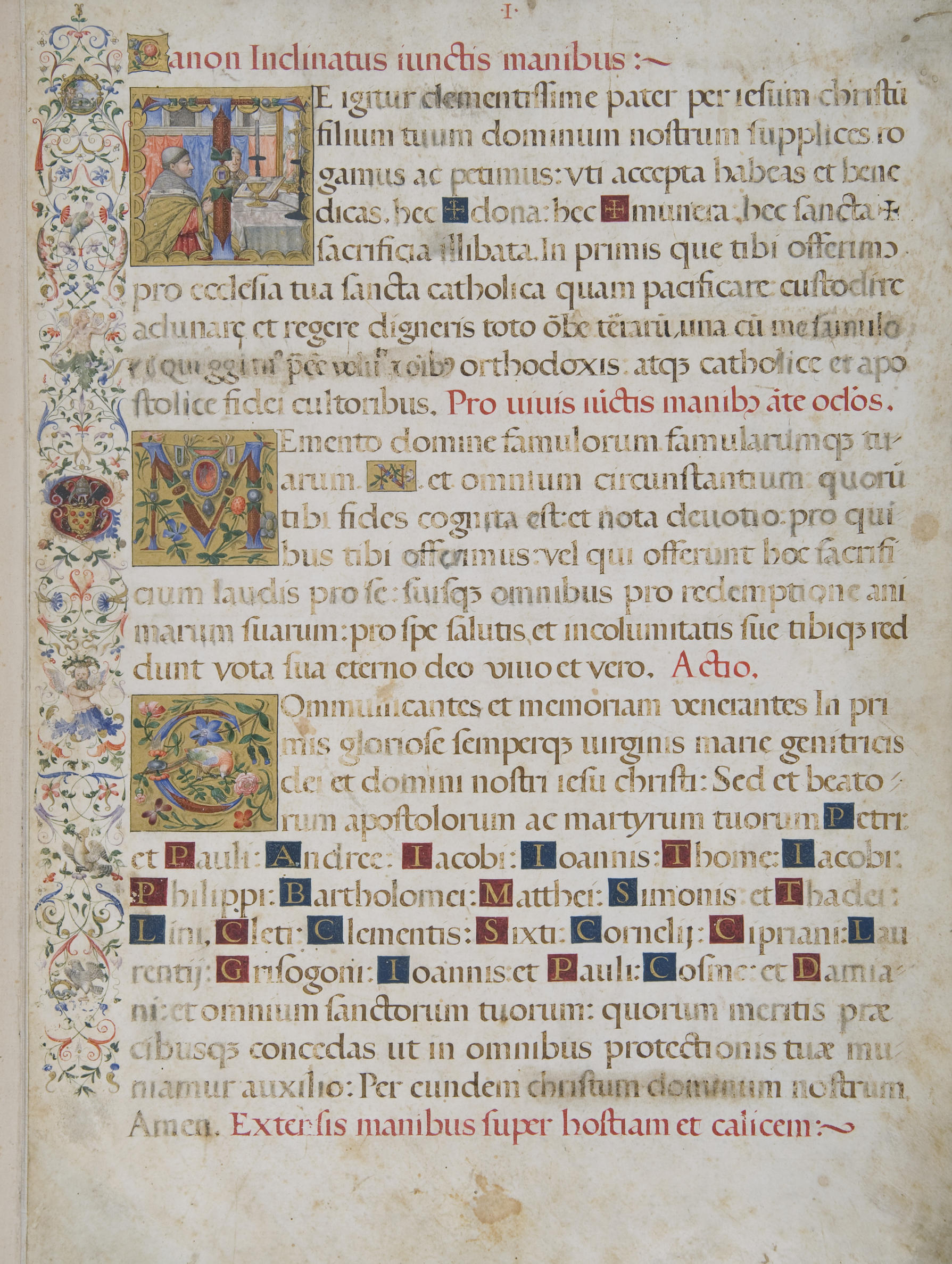

Buried deep in the Museum’s Tapestry Room, surrounded by sets of monumental tapestries and shrouded in shadow, sits a small gathering of vellum pages. Black, red, blue, and gold text covers its surface, vines creep along the edges, and one illuminated letter opens a window onto a tiny painted world.

Illuminated letter “T” from a Missal of Pope Clement VII, 1523–1527, by Master of the Missal of Cardinal Bernardino De Carvajal (active Rome, 1520s)

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston. See it in the Tapestry Room

Look closely at the top left, behind the letter “T.” Two men stand in front of an altar covered by a cloth and supporting an open book, a chalice and a pair of candlesticks. In the background, you can just make out a decorated wall behind the altar.

Sebastiano del Piombo (Italian, 1484–1547), Giulio di Giuliano de' Medici, Pope Clement VII, about 1531

J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

The scene playing out before us is no ordinary church service. The man on the left is Pope Clement VII (reigned 1523–34), identified by the coat-of-arms in the margin. Standing before the altar and accompanied by an assistant, he celebrates this Mass in the Sistine Chapel. The artist, known as the Master of the Missal of Cardinal Bernardino de Carvajal, imagined the event in exacting detail. The sliver of the wall behind this altar reveals a glimpse of The Assumption of the Virgin fresco by Renaissance painter Pietro Perugino, eventually destroyed by Michelangelo to create his Last Judgment. Michelangelo did not just remake the back wall of the chapel, but also the ceiling, frescoing over an existing ceiling painting of a starry sky by painter Piermatteo d’Amelia, whose work is represented in Gardner’s collection.

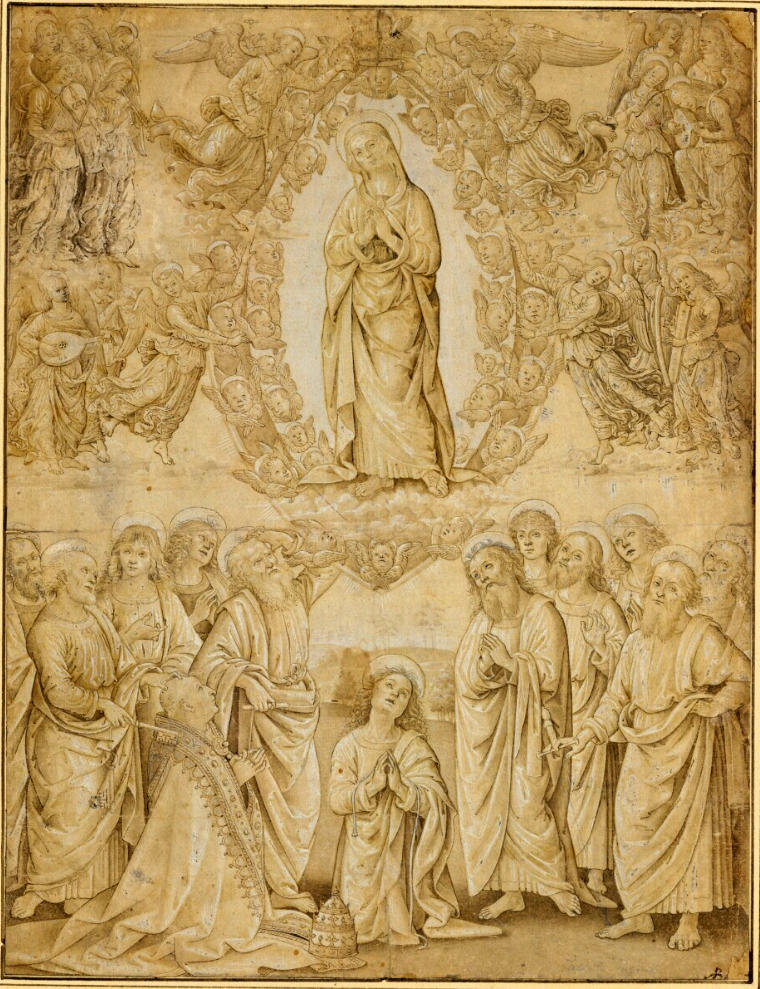

Drawing by Pinturicchio (Italian, 1454–1513) of Perugino's lost fresco Assumption of the Virgin in the Sistine Chapel, 15th century

One of several, this page was cut from a Christian service book called a missal. It was commissioned by Pope Clement VII to celebrate Mass in the Sistine Chapel. The Latin text gives instructions to the priest. The opening line of this one—inscribed in red at the top of the page—reminds the celebrant to incline his hands as he begins the service. Symbols then guide him through it. Small “+” symbols remind him when to make the sign of the cross.

Leaf from a Missal of Pope Clement VII, 1523–1527, by Master of the Missal of Cardinal Bernardino De Carvajal (active Rome, 1520s)

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston. See it in the Tapestry Room

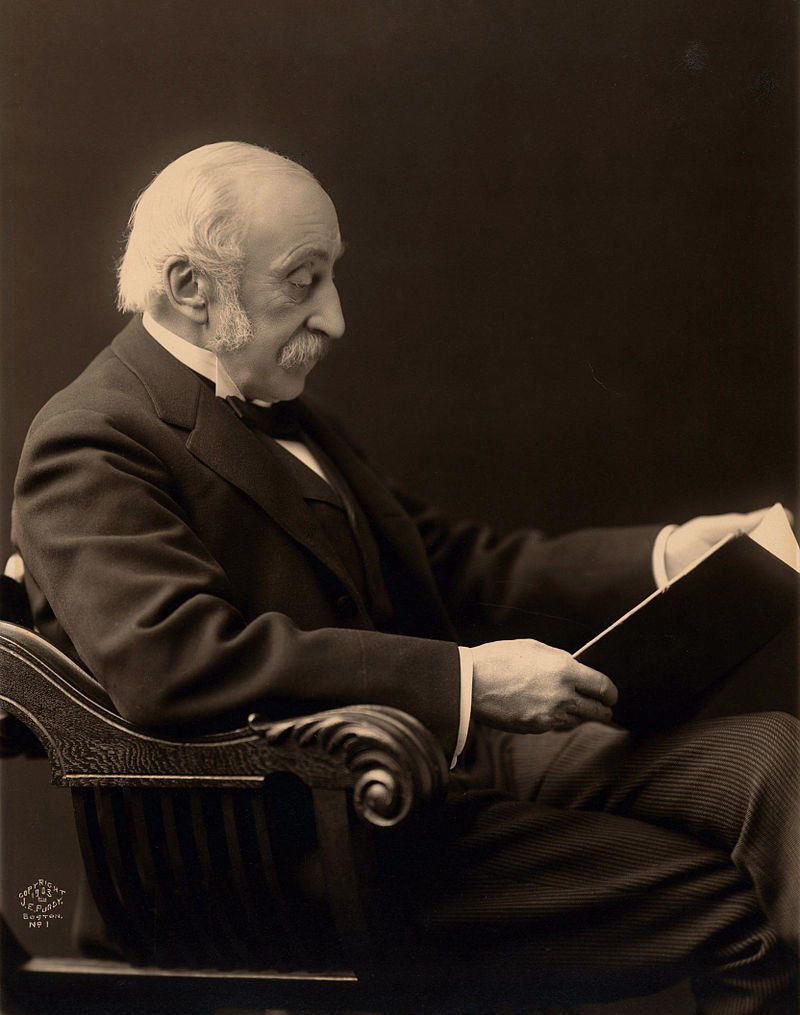

In 1798, during the French occupation of Rome, looters likely stole this book from the Vatican along with many other Sistine Chapel manuscripts. Like several others, it was cut into pieces and sold on the art market. Little is known of this book’s journey from Rome to Boston, save for the fact that it was in a private collection in London in the late 19th century. In 1904, Isabella Stewart Gardner purchased this fragment from her friend, Harvard professor Charles Eliot Norton.

James E. Purdy (active Boston, early 20th century), Charles Eliot Norton, 1903

Houghton Library, Harvard University

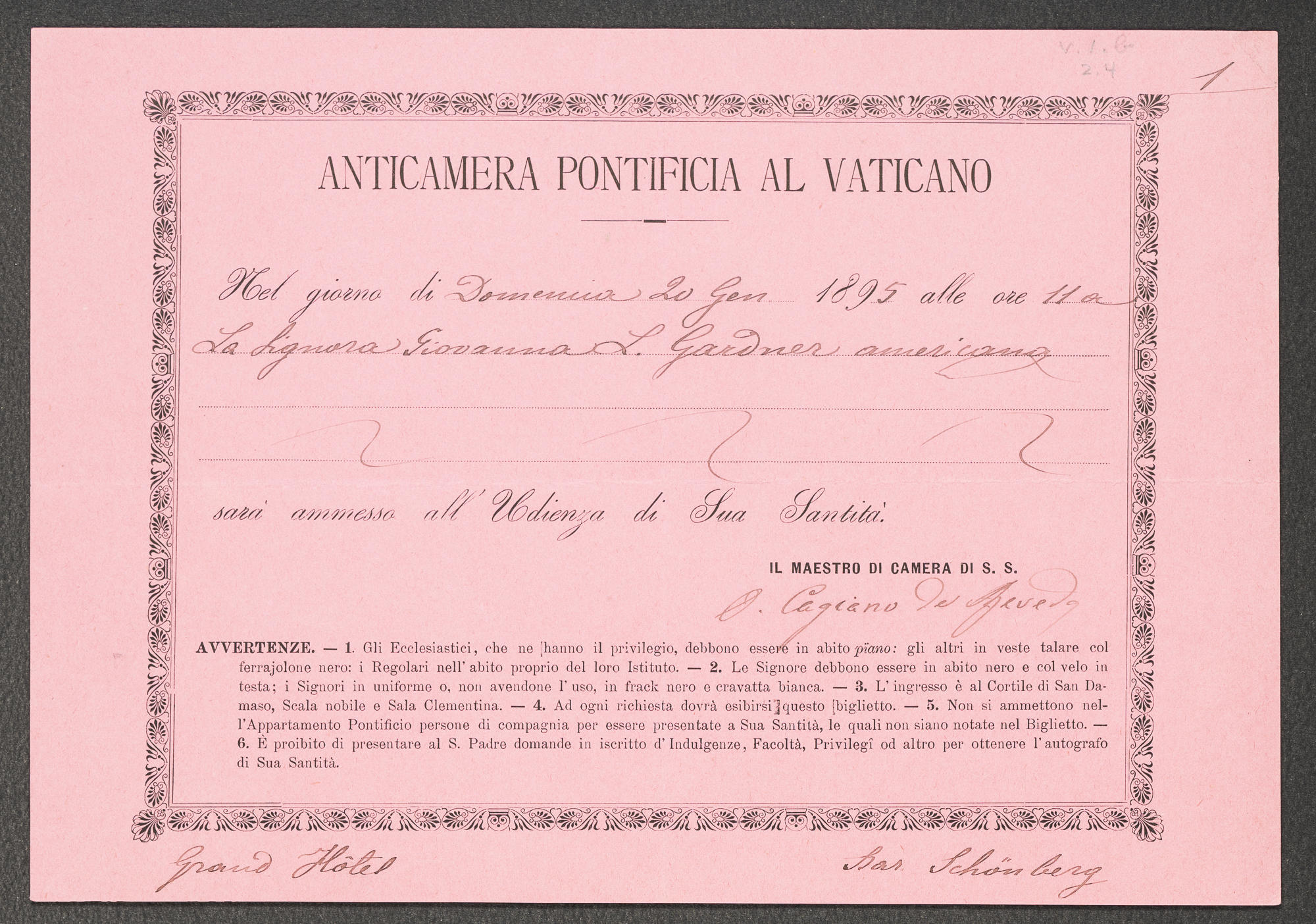

Fascinated by religion, Isabella not only collected relics of the papacy but once met a pope in person. On the Gardners’ 1895 trip to Rome, they stayed several months so that Isabella could secure an audience with Pope Leo XIII. Just like Sharon Stone in HBO’s The New Pope, Isabella dressed the part. She stopped in Paris on her way to Rome to collect a magnificent black dress from her favorite designer Charles Frederick Worth. Upon arrival in the Eternal City, she made enquiries, ultimately leading to a formal invitation from the pope for a personal audience, the rarest of privileges.

On 20 January 1895, Isabella headed to the Vatican alone—Jack spent his afternoon at the American Church in Rome. When she arrived at the pope’s residence, she found him sitting beneath a window. She wore the stunning new outfit from Paris. He beckoned her to approach, and she kneeled at his feet. They talked for some time. His Holiness asked Isabella many questions about the United States, as well as about her Anglican faith and her art collection. When she told him about the Sistine Chapel manuscript, he asked to see it, saying, “The next time you come to Rome, bring the missal with you and show it to me yourself.”

Certificate of Isabella’s audience with Pope Leo XIII, 20 January 1895

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston (ARC.008913). Isabella kept this certificate in the Vatichino, her personal treasure trove

News of Gardner’s celebrity audience with the pope quickly made its way back to her friends and became a legendary encounter. Henry James remarked enviously that she had “captured” the pope with charisma, charm, and celebrity. Gardner’s friend, the Museum of Fine Arts trustee William Sturgis Bigelow wrote to her, “The stories that have reached us of your having the Pope & Humbert [King Umberto I of Italy] to tea together.” Like any good rumor, it was only partly true, but Isabella cherished her memories of the audience and wasted no time in sharing them. Upon returning to Boston, she and Jack went out for dinner with Thomas Russell Sullivan—who penned the stage adaptation of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde—and regaled him with the tale. Thanks to Sullivan’s published diary we have the full story, straight from Isabella herself.