If you have visited the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, bring to mind the museum’s courtyard garden. Perhaps you imagine verdant foliage punctuated by bursts of flowers in full bloom, tall walls rising to a glass roof, or figures sculpted in white marble. You probably do not picture a large mauve triangular banner, emblazoned with a gold dragon, hanging from a pole high above the north side of the Courtyard. (If you do, please get in touch with the Museum’s Collections Department.) However, such a dragon banner appears in the museum’s early inventories that record the objects in the collection and where Isabella installed them. The Museum recently reinstalled a replica of the banner, and this is the story of the banner’s history and its reproduction and reinstallation today.

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston

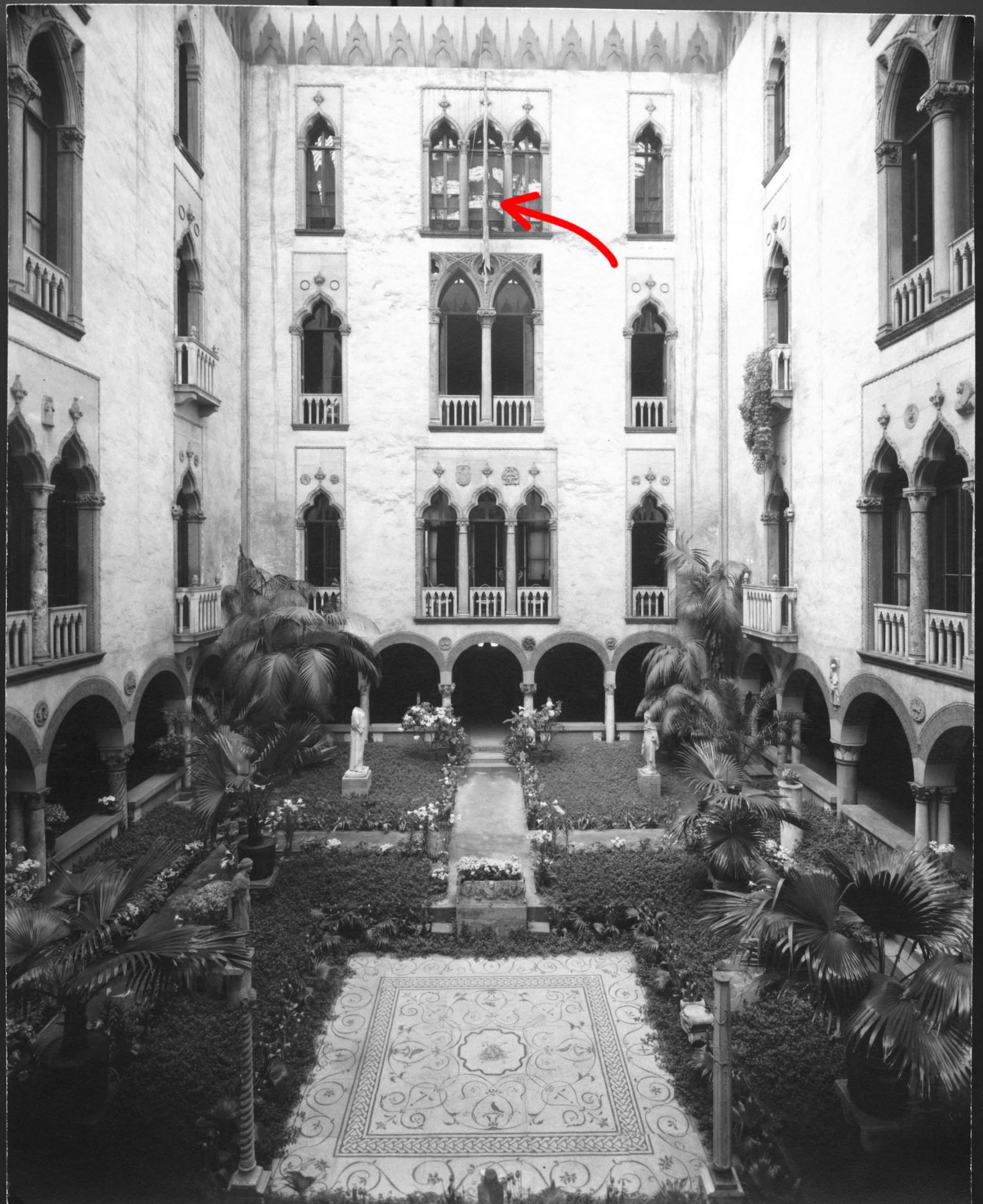

The reproduction dragon banner hanging from fourth floor windows overlooking the Courtyard, January 2025.

Tracing the Dragon Banner

Shortly after Isabella Stewart Gardner (1840–1924) died, museum staff and consulting experts carried out a series of cataloging campaigns and recorded them in dozens of binders collectively called the Inventory and Notes (I&N). The I&N sought to both identify objects and record exactly where Isabella installed them.

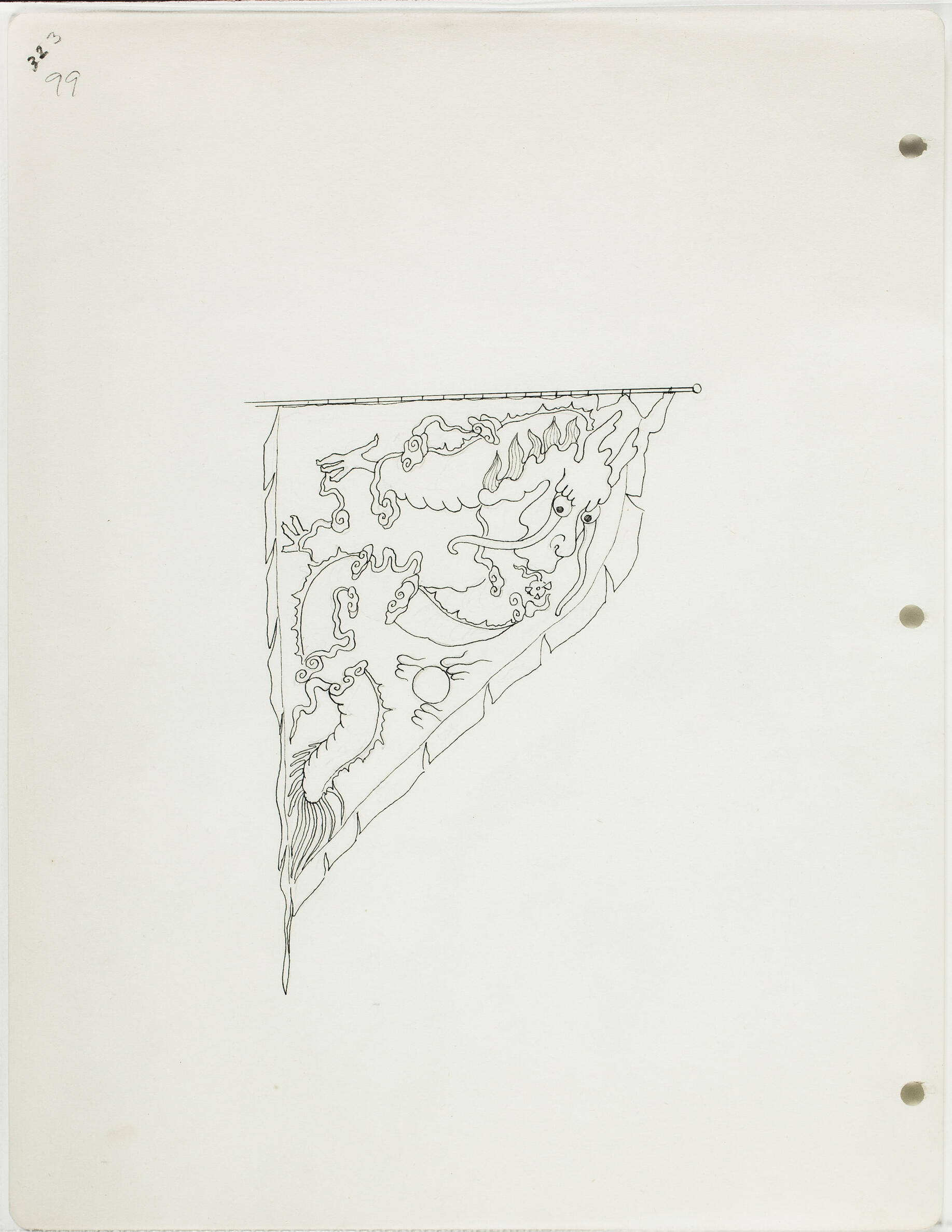

The dragon banner appears in the museum’s 1927 inventory of art from Asia, illustrated by Shun’ichiro Tomita four years after Isabella’s death. Shun’ichiro Tomita was a relative of Kojiro Tomita (1890–1976), a curator of Asian art at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston (MFA) and an acquaintance of both Isabella Stewart Gardner and Okakura Kakuzō (1863-1913). Shun’ichiro Tomita’s line drawing shows the banner as it hangs by its shortest side from a flagpole, with the dragon’s head turned toward the ground.1 The banner makes two more appearances in historic photos of the Courtyard. In one photograph from April 1938, the banner is barely visible in a head-on view of the north wall. In another photograph from the early 1950s, an image of the banner is visible from the side. In these pictures, we can see more clearly that the banner hung from a flagpole outside a fourth floor window, above the Titian Room.

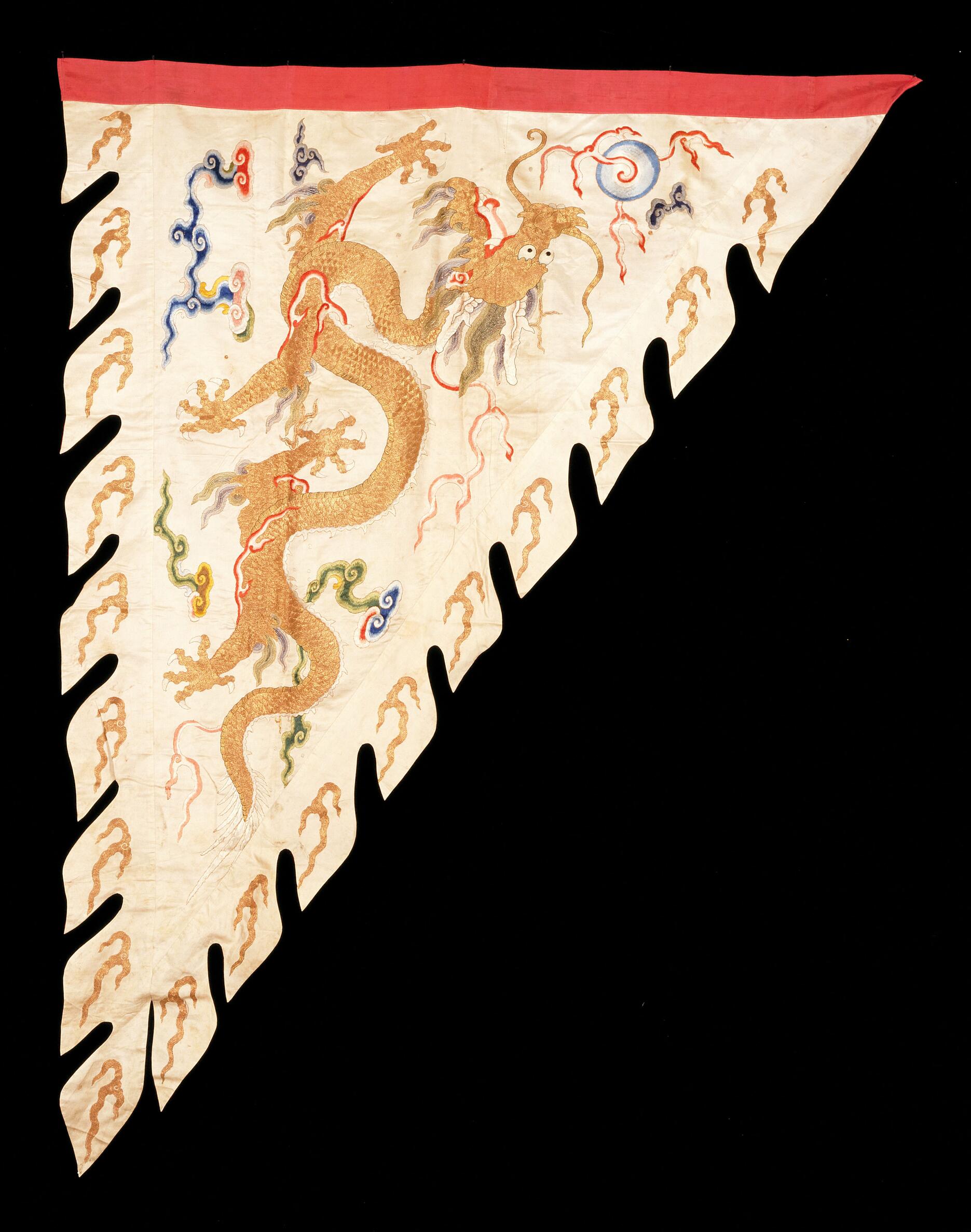

There are also a few textual descriptions of the banner. Interestingly, the text accompanying Tomita’s 1927 drawing details that the banner hung in the Courtyard from the northside of the fourth floor. The text goes on to specify that the banner is Chinese, it should be dated to the early 1800s, and the dragon is embroidered on a “yellow (faded) silk.”2 This last note about the yellow silk ground is notable because when textile specialist Ella S. Siple from the Worcester Art Museum described it slightly later, between 1927–1930, she described a “soft-violet” ground and that “the background has been entirely restored.”3 Museum conservation records show that the banner underwent several rounds of conservation and restoration in 1929, 1934, and 1954, before it was put into storage in 1955. Thus, the replica we have created is based on the heavily restored banner—meaning it can only approximate its appearance from when it entered the collection.

Someone also made a note in the I&N that the banner was a gift of artist, professor, and Asian art collector Denman Waldo Ross (1853–1935).4 It is unclear how the compilers of the inventory knew this, as there is unfortunately no other record in museum archives of Ross giving a dragon banner to Isabella, or where and when Ross acquired the banner.

There is one tantalizing suggestion of someone seeing the dragon banner installed during Isabella’s lifetime. The reference to the potential sighting can be found in an undated letter, probably from around 1919, from Ruth Von Scholley (1893–1969) to Isabella. Ruth writes:

I am still overwhelmed at the beauty of this wonderful Chinese hanging—it is possible that you remember my admiring it last year that day when [we] lunched with you and had coffee and funny cigarettes with straws up in your boudoir? … Someday I hope you’ll tell me where it came from & how you got it & everything about it.

Because the 1924 inventory of the fourth floor apartment, where Isabella lived from 1901 until her death, does not include any Chinese hanging textiles,5 and because Ruth would have walked by the fourth floor windows where the banner was installed on her way to Isabella’s “boudoir,” there is a chance that Ruth is talking about the dragon banner.6

What kind of banner is it?

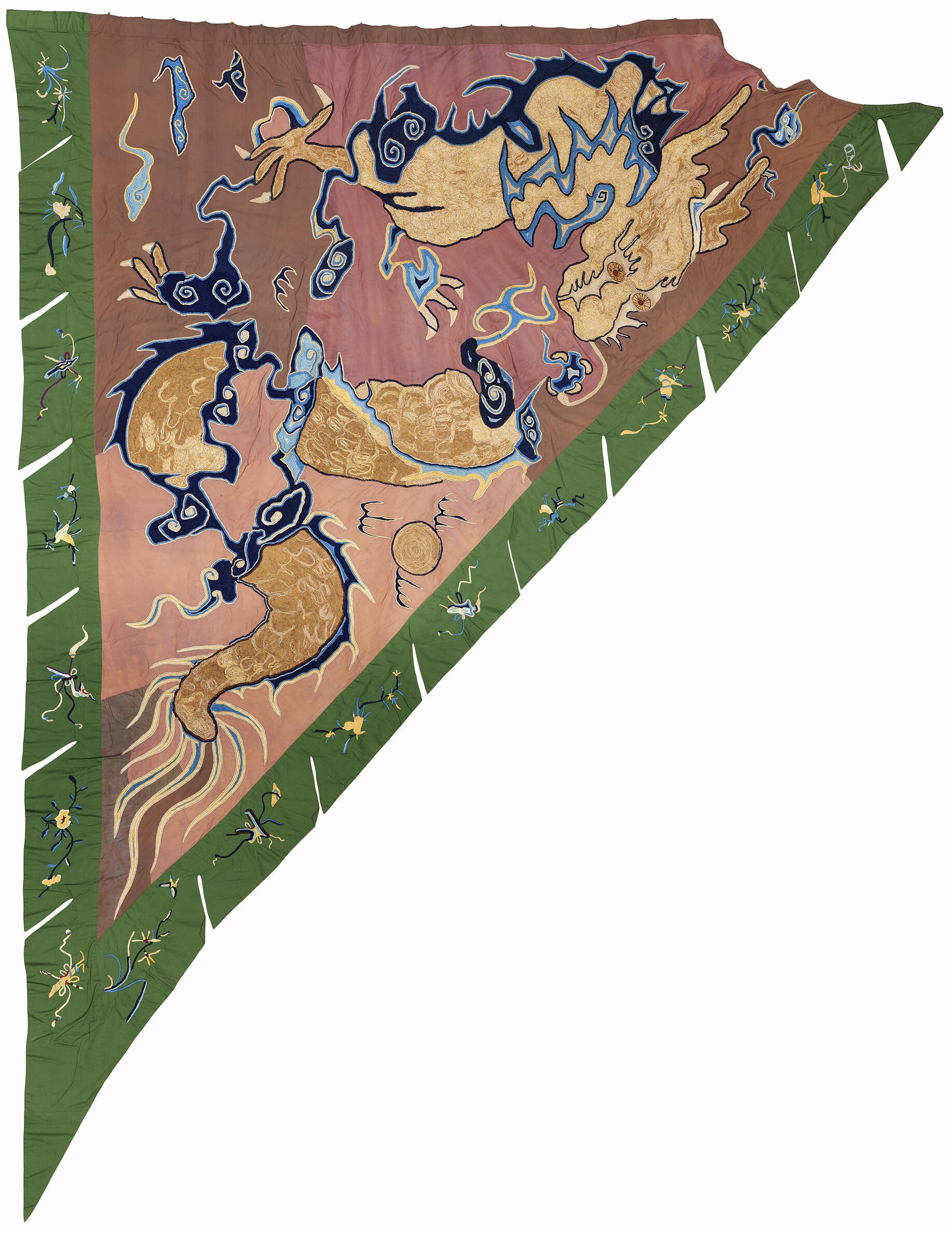

The banner is heavily restored, but it is embroidered on both sides with a dragon in metallic threads, surrounded by wisps of blue clouds and a flaming spherical jewel. Three of the dragon’s claws are visible, one with four digits and two with three digits, while the dragon’s curling body is divided into four segments. The two long edges of the banner have a serrated green border that is embroidered with heavily repaired motifs, likely ones associated with the Eight Daoist Immortals.

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston (T26sip50)

Chinese, Dragon Banner, early 19th century. Embroidered silk, metallic fibers, 406.4 x 335.3 cm (160 x 132 in.)

The Gardner banner’s triangular shape, flanged edges, and gold dragon evoke Qing dynasty (1644–-1911) banner system flags. These flags, see for example the Manchu Military Banner of the White Banner Regimen from the Minneapolis Institute of Art (MIA 42.8.282), were used in “ceremonies and military reviews...rather than in battle.”7 However, in its size, style, and color, the Gardner banner is different from the Minneapolis example. It is possible that the Gardner banner is related to the “Celestial Dragon Flags” catalogued as part of the Hubei Province exhibit at the 1904 Louisiana Purchase Exposition held in St. Louis8. Listed alongside military tents, swords, and suits of armor, “Celestial Dragon Flags” are described as “used on the occasion of State functions” and made of “Imperial yellow” silk with a “green border”—similar to early descriptions of the Gardner flag.9

However, it is uncertain if the Gardner’s example was created as a military or court banner. Triangular dragon flags were also created as stage decorations and collected by Americans in the early 1900s. For example, in 1923 curator Berthold Laufer (1874-1934) collected a number of Chinese theater props, including triangular dragon banners, now in the Field Museum collection in Chicago.10 Like the Minneapolis example, the Field Museum work is also different in style, size, and composition from the Gardner example, but together they demonstrate the range of dragon banners collected by Americans in the 20th century.

Reinstalling the Banner

Because the original dragon banner has been in deteriorated condition since the 1950s, it would not be safe to re-install. Using new photography of the original banner, the museum printed a to-scale reproduction on textile. The reproduction will be hung in the Courtyard on the north wall, outside the fourth floor windows.

We may never know the exact origins or story of this banner, but it is notable that Isabella Stewart Gardner placed a Chinese object—or an object that evokes China—in the center of her central Courtyard. The installation of this dragon banner reproduction helps to remind us that Isabella’s ideas about Asian art and culture are key elements to understanding this museum.

You May Also Like

Read More on the Blog

Listening, Learning, Meditating: Isabella’s Journey with Chinese Art

Read More on the Blog

Making Reproductions of Two Hanging Scroll Paintings

Read More on the Blog

Joseph Lindon Smith’s Chinese Theater

Notes

1Kojiro Tomita, Catalogue of Asian Art, Sun-Ichiro Tomita (Illus.), 1927. Unpublished manuscript, Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston. 99-100.

2Tomita Illustrated Inventory of Asian Art, (1927) Pages 99-100

3Ella S. Siple. Around 1927-1930. Isabella Stewart Gardner Conservation Report for T26Sip50.Unpublished report, Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston, MA.

4Denman Ross was an artist, an art theorist, and a collector of Asian art in Boston. Ross traveled to China in 1910 where he visited major cities including Beijing, Nanjing, and Shanghai. See Patricia Ross Pratt, The Life of Denman Waldo Ross, The Best of its Kind: Teacher, Collector, Painter 1853-1935 (Northern Liberties Press, 2020) 112.

5Trustees of the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum (established Boston, 1900 - ), Executors Inventory of Fenway Court, 1924. Ink on paper, Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston (ARC.007329) The fourth floor inventory, compiled in 1924 includes one pair of “Chinese embroidered panels” in Isabella's bedroom. However, Isabella’s bedroom was a separate room from her boudoir where Ruth visited.

6It should also be noted that in 1919, Ruth Von Scholley, who was a painter, gave Isabella a painting titled Birth of a Dragon. In this painting, the serpentine body of a black dragon with four-digit claws runs across the exterior of a yellow bowl, while figures conjure a vaporous dragon from the vessel’s interior. In the painting, it seems that Von Scholley is attempting to depict figures in East Asian dress, but her depiction lacks both specificity and accuracy, resulting in a caricature of East Asian people. The dragon vessel in the painting bears a resemblance to a metal Japanese bowl installed in the museum’s Tapestry Room. It is a suggestion that Ruth’s painting and her fascination with dragon imagery may have intersected with objects in Isabella’s collection.

7Manchu Military Banner of the White Banner Regiment, Minneapolis Institute of Art Online Collection, 42.8.282. Accessed March 15, 2023. Official Qing triangular dragon banners can be seen in paintings from the 1700s, like the Beijing Palace Museum’s Mashu tu 馬術圖 by Giuseppe Castiglione (1688-1766), a Jesuit painter at the Qing court. Thank you to Professor Mark C. Eliott for sharing this painting, as well as his expertise on the Manchu Military Banner system. For reading on the Banner System, see Mark Eliott’s The Manchu Way: The Eight Banners and Ethnic Identity in Late Imperial China, Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2001.

8Thank you to Professor Bob Murowchick for the reference to this catalogue for the Chinese Exhibits at the Louisiana Purchase Exposition of 1904. To learn more about Asia at the World’s Fairs, see this online exhibition co-curated by Professor Murowchick.

9China: Catalogue of the Collection of Chinese Exhibits at the Louisiana Purchase Exposition, St. Louis, 1904. Published by the Order of the Inspector General of Customs (St. Louis: Shallcross Print, 1904) 144.

10Thank you to Nancy Berliner, Senior Curator of Chinese Art at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston for taking a look at the banner and highlighting a potential Field Museum connection.